A consensus among Rowan students seems to be that the Wellness Center isn’t sufficient when it comes to addressing student mental health. These feelings are valid, and come from an honest place of frustration. After all, nobody wants to deal with a three week intake period before their counseling begins, or end up in a program that they don’t think will work for them.

But The Whit urges students to understand that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to mental health — and that the services offered by the Wellness Center are effective for a large population of Rowan’s community which receives them.

For many students, the Wellness Center is their first opportunity to receive low cost, accessible mental health services. Most likely cannot afford the cost of an off-campus therapist or counselor. Many likely come from home environments where lapses in mental health are stigmatized, and where family is unwilling to provide support.

A student in crisis, who is likely suffering feelings of hopelessness and helplessness, will probably not be helped by campus wide hyper-fixation about how the one service available to them will be a waste of their time. The only impact will be to convince that already vulnerable student not to reach out at all.

It is downright irresponsible, and often comes from a place of high privilege, to suggest that the Wellness Center isn’t valuable.

For many students discontent with the Wellness Center, these feelings come from anecdotes of being “turned away” when trying to enroll in packed individual counseling programs; they say that the source of their bitterness comes from being suggested group therapy, an inpatient program, medication or a program which is currently being used as a trial study.

But students aren’t being “turned away” just because the treatment which is recommended to them isn’t what they envision for themselves. Many of these same disgruntled students had access to one-on-one therapy sessions prior to coming to college. Others are just informed by media portrayals of “real,” “effective counseling” comprised of laying on a divan while getting psychoanalyzed, and see anything else as second best. Many have probably never actually tried the treatment plan that they are being recommended. All that they know is that they’re not getting what they want.

For many other students, symptoms of their mental illnesses may impact their abilities to go through with the steps of enrolling in counseling programs. Emotional dysregulation may make the disconfirming feedback associated with many kinds of treatment especially painful, causing students to drop programs they actually need. Meanwhile, depression can impact the executive function necessary to remember appointments, let alone attend them. On this, the current model of American mental health treatment privileges those who are already more functional and able to better cope with symptoms.

These intrinsic barriers to treatments are huge and absolutely need to be discussed in context of improving the model of counseling in America — but they’re not barriers unique to Rowan or the Wellness Center. They’re certainly not a product of apathy from the staff there.

The problem doesn’t seem so much to be that the Wellness Center needs to be doing more to act like a private therapist’s office, but that they need to find a way to make expectations match reality. In issues of mental health, the rift between those two things can be cavernous.

While education of mental health disorders has increased in recent years, and with the advent of social media, public education of mental health treatment seems to be slow to catch up. After all, it’s estimated that over half of the population thinks that electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is akin to torture, based on media representations such as in the movie “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” when, in fact, modern ECT is shown to be one of the safest and most effective methods for treating depression.

The Wellness Center doesn’t offer ECT, but it does offer other often misunderstood treatments in the form of group counseling, drop-in counseling, crisis counseling and substance abuse counseling, as well as individual counseling.

There are many different kinds of groups that students can join, including those for Dialectical Behavioral Therapy, Radically-Open Dialectical Behavioral Therapy, Anxiety Toolbox, Body Kindness, Koru (Mindfulness and Meditation), Connections in Color, LGBTQ+ Supportive Therapy, Overcoming Grief and many others.

Any given group may be helpful and applicable to any given student, and there’s research to prove this. An armchair psychologist of an undergrad is not qualified to make claims against the global effectiveness of group counseling, especially when these claims are based on misunderstandings fueled by social stigmas.

Our population has been empowered with the knowledge of illness. But it is impossible to treat the illness when there is such pervasive misinformed perception about the treatments.

It is impossible to treat the illness when you have waged a war against the treatments, without giving them a fair chance to help you.

It is impossible to treat the illness when you are poor or lack a support system, and the one resource available to you is being vilified by those who can afford to seek an alternative.

There are many productive conversations that could be had about the insufficient resources that the university allocates towards mental health resources. These generative discussions are what made possible the health initiative which eliminated copays for all student health services, replaced with a $30 fee on tuition. Such changes worked to make services more accessible to all students.

The Wellness Center will only become more effective when the student body throws its support into it. Why would university bureaucrats want to fund the Wellness Center, when all that they’ve heard from students are negative experiences? Wouldn’t a more helpful approach be to advocate for making the many positive student experiences accessible to a wider portion of the population?

So, if you’re a student with a negative opinion with the Wellness Center, The Whit urges you to think critically before publicizing your thoughts. Does this criticism help another student, who may be listening, navigate mental health treatment while at Rowan, or could it potentially harm them? Is this criticism in response to lived experiences related to the effectiveness of treatments, or is it based on perceptions of treatments you’ve declined? Are you turning an anecdotal experience into one claiming to represent a typical sample of students?

We understand where these criticisms are coming from, but ask that you understand where they’re going.

Mental health resources on Rowan’s campus have a long way to go before they are perfect for accommodating such a rapidly expanding student population. On that, most students and faculty would probably agree.

But there are resources. There are places and people that will help offer to help you, both inside and outside of the Wellness Center’s offices. The thing about offers, though, is that they have to be accepted.

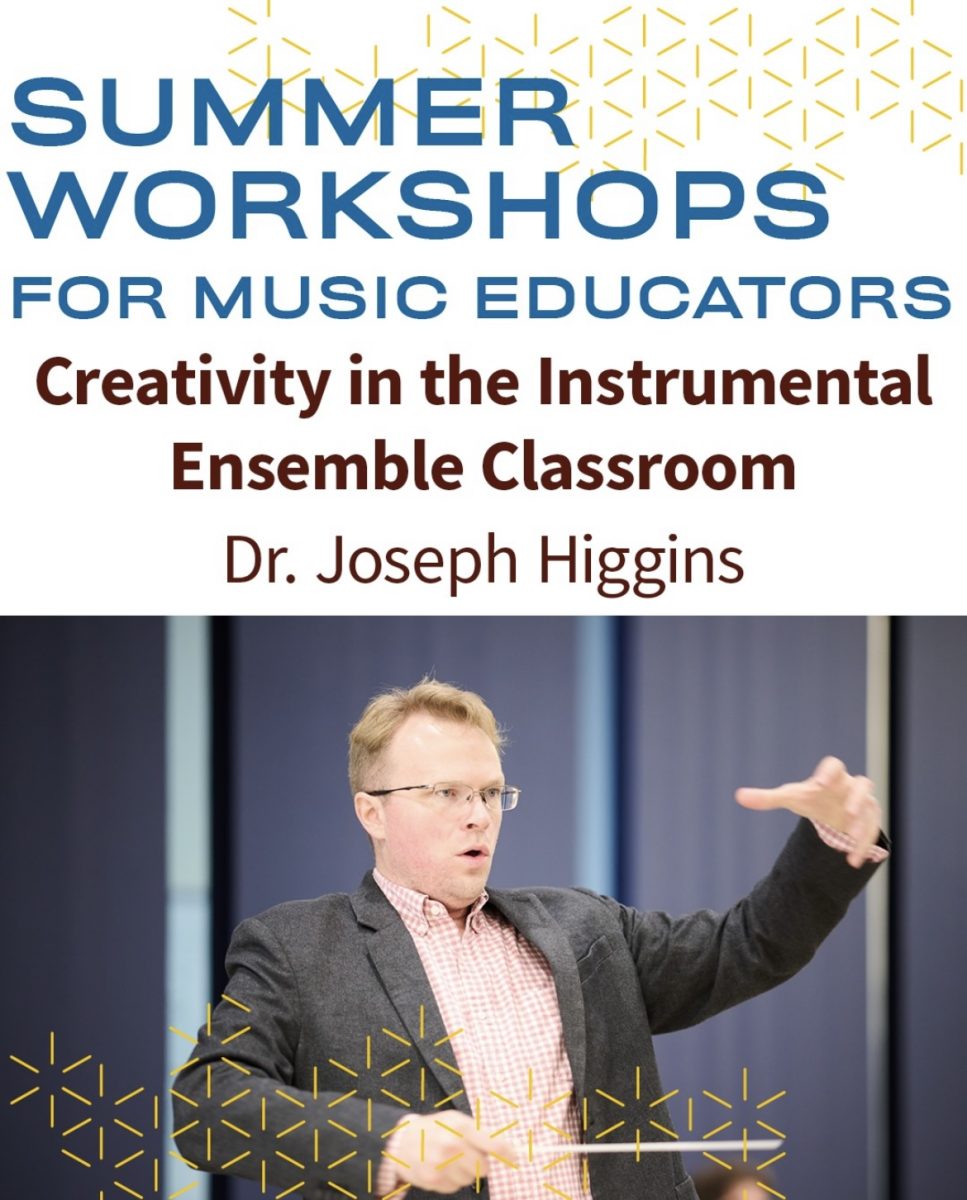

!["Working with [Dr. Lynch] is always a learning experience for me. She is a treasure,” said Thomas. - Staff Writer / Kacie Scibilia](https://thewhitonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/choir-1-1200x694.jpg)