Editor’s Note: This op-ed contains discussion of suicide and mental health issues, and may be distressing or triggering for some readers. This article has also been updated to include information about contacting the National Suicide Prevention Hotline at 1-800-273-8255.

Today, I took a longer path than usual after leaving the Rowan Boulevard parking garage.

Usually, I take the elevator across from Chickie and Pete’s and book it for the class I’m usually late to. But today, with mental health fresh on my mind from some sudden university news, I went around back by the Rowan Boulevard Apartments and up the infamous alley between the parking garage and Barnes and Noble.

I knew some things about what had happened. I knew this was where, in December 2017, just two weeks before Christmas, a boy died of suicide by falling from the sixth floor of the parking garage.

I knew that the tragic scene had been found and “dealt with” by police and university officials early that next morning and essentially swept under the rug with a tight little Rowan Announcer and never mentioned again. I knew he had had a twin brother on campus somewhere that year, someone who is undoubtedly still mourning his loss to this day.

I knew he had parents who were doing just the same, who insisted to inquiring minds that the bare minimum information about their lost son be shared with the public, a completely reasonable request that was presumably granted without protest.

I knew he must have been hurting in such deep, unimaginable ways.

I knew he had deserved better.

I stood there in the alleyway between classes, staring at the spot where they must have found him, trying to feel what he had been feeling, and ultimately failing. It was almost 6 o’clock at that point, peak commuter time for Rowan Boulevard, and I knew I must have looked pretty odd standing alone in the middle of the alley and staring up at the top level of that parking garage, but I couldn’t bring myself to pull away just yet.

I tried to imagine the pain he was in, the anguish he must have felt for so long that lead him to believe he was left with only one final option.

I didn’t know his name.

In that moment, it felt wrong to take out my phone and try to find out who he was. I wanted to just take a moment to acknowledge the human being who had fought the hardest fight. Who, feeling alone and helpless, came to his abrupt and undeserved departure from his family and loved ones, because of something that he should have had the resources and support to prevent.

I knew I could never truly understand what he was going through.

He wasn’t the first student to lose their life to suicide during my time at Rowan. Janette Garriga, a 27-year-old clinical psychological doctoral student, was found dead in her on-campus apartment on April 26, 2017. This, too, was swept under a rug with an email to students and encouraged students having difficulty with the news contact the Wellness Center to speak with a counselor, but nothing else was mentioned about her.

In fact, her mother later tried filing a lawsuit against the school, saying that several months after her daughter’s suicide, she became aware that “professors and counselors at Rowan University may have pressured (her daughter) to take her own life.” However, the state appeals court ruled that she could not move forward with the lawsuit since she missed a legal deadline by 17 days.

In the wake of the news of yet another student’s “sudden passing” being relayed to students through an email, I find myself in a another vat of confusing emotions. I’m devastated, I’m angry, I’m perplexed. But overall, I’m exhausted.

Admittedly, this “sudden incident” is currently not known to be a suicide, and under strict HIPAA Privacy Rule guidelines, details won’t be released to the public without parental consent, but the ambiguous email had myself and many others convinced it had something to do with mental health issues.

Mental health services at Rowan University were a large part of why I chose to come here in the first place. As someone who grew up with and continues to manage major depressive and generalized anxiety disorders, it was important to me and my parents that whatever school I decided to go to had ample mental health services if something were to happen, whether that was just having support on a rough day or as far as having a lifeline in a crisis.

When I took my first tour of campus with my mom, we were assured as we passed the Wellness Center that Rowan had counselors ready at all times for students in need.

But over my four years here at Rowan, I’ve seen very little of those promises be really fulfilled.

I remember small things being done in light of the growing mental health crisis over my four years here at Rowan. I remember how in my sophomore year they added the crisis helpline to the back of student IDs. I remember when they put up “Are you in crisis?” signs on all the doors to the Rowan Boulevard parking garage.

They’re all just band-aid fixes to a much more serious problem.

And I, as well as others, were quick to believe our community’s newest lost involved mental health concerns because we are all aware of the poor excuse for mental health services Rowan University has given us thus far.

This is certainly not just Rowan that has this problem or similar issues, as universities across the nation are undoubtably managing similar problems regarding mental health services for students.

But more and more these cries for better help are instead met with spectacle, glamorizing the problem and sparking talk of change for the moment, only to be quickly forgotten about by the end of the week.

According to the Press of Atlantic City, the Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors found in an annual survey that about 66 percent of people on campuses in the 2016-17 year said counseling services helped with academic performance and 65 percent said these services helped them stay in school.

In this same article, Vice President for Health and Wellness and Director of Counseling and Psychological Services at Rowan University David Rubenstein said that the Wellness Center had increased from 20 staff members to 60, including 15 behavioral health counselors. He even went on to mention that Rowan has been placing counselors in high-traffic academic buildings and centers, most likely referencing Rowan’s “Let’s Talk” program, a service open to all students that provides various drop-in hours at different sites on campus.

I’ve personally tried this service twice in my time at Rowan. Most recently, I waited almost fifty minutes for a “drop in” appointment, and by the time the single counselor for the day’s service had reached me, there were only ten minutes left for her hours that day.

The first time I tried to use this service, a day that I was truly in crisis and needed a lifeline, I was told that the program session was cancelled for that day and turned away.

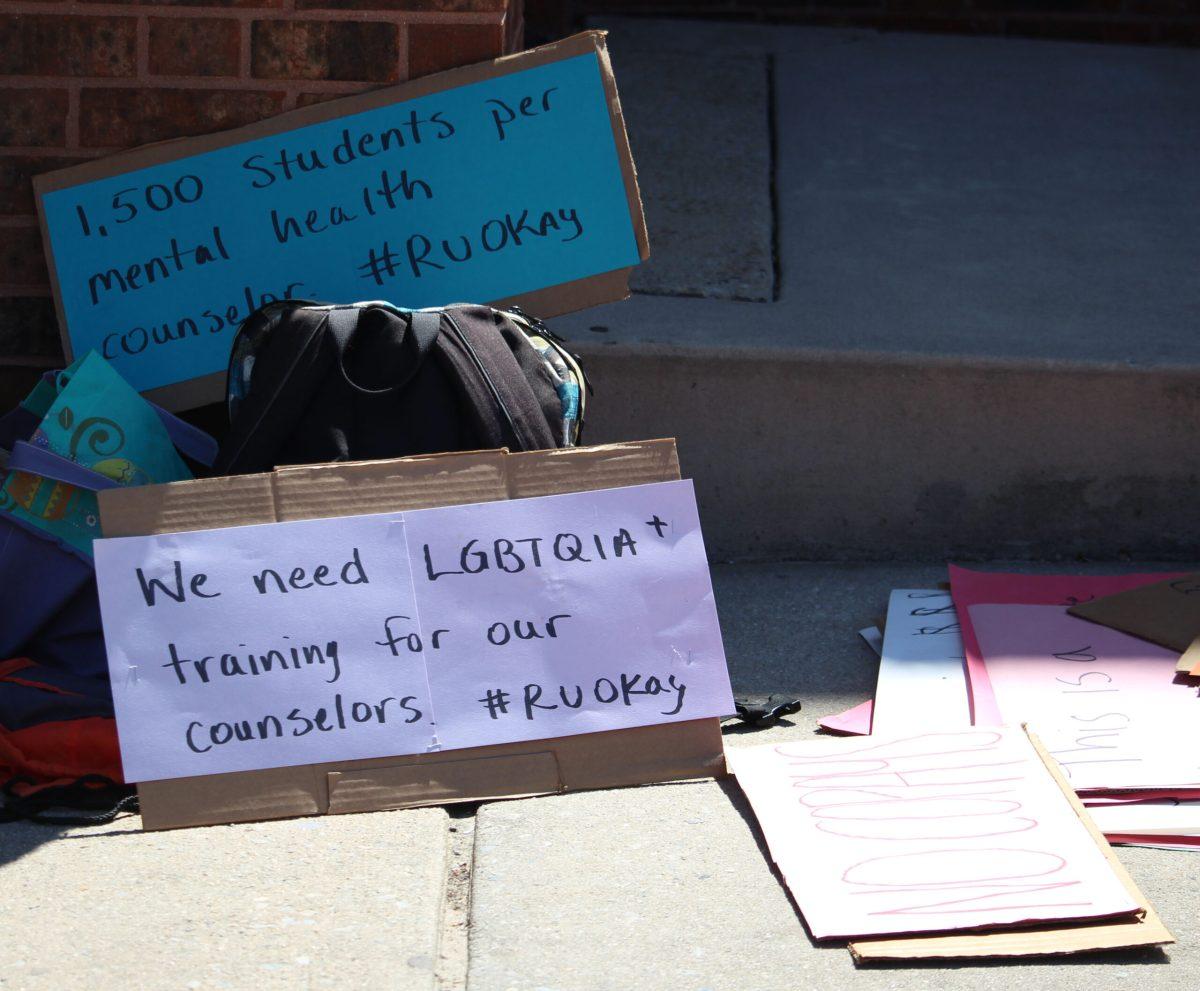

Rowan students have even gone so far as to protest health services at the Wellness Center before. Last year during Hollybash, students gathered outside the Wellness Center to protest the new copay for medical services Rowan had recently presented.

Rowan listened, and instead of requiring copays for visits added $30 to student tuition to cover these expenses.

But there are issues at the Wellness Center that haven’t been addressed. In 2017, there was a semester-long waitlist at the Wellness Center to get into counseling services. Several students reported being turned away or asked to join group therapy instead of individualized sessions, something many people reaching out are in need of over generalized support.

Though I guess it can’t be all bad. After all, Rowan University did get a $3 million donation to establish The Schreiber Family Pet Therapy Program of Rowan University. Next time me or someone I know are having a crisis and need help, I’ll be sure to send them to the pups, instead. That’s sure to work, right?

I did look up his name once I made it to class (a little late, but nothing too bad). His name was Ryan Onderdonk. He was a senior communication studies major.

Ryan Onderdonk deserved better.

We can all help prevent suicide. The Lifeline provides 24/7, free and confidential support for people in distress, prevention and crisis resources for you or your loved ones, and best practices for professionals. 1-800-273-8255

For comments/questions about this story, email [email protected] or tweet @TheWhitOnline.

!["Working with [Dr. Lynch] is always a learning experience for me. She is a treasure,” said Thomas. - Staff Writer / Kacie Scibilia](https://thewhitonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/choir-1-1200x694.jpg)