Rowan students were educated on various types of exclusionary feminism, as well as the history of violence and legislation directed toward Asian women, during the virtual lecture series “Theorizing: Tamsin Kimoto on Exclusionary Feminisms,” on Wednesday, March 24.

This event was a part of Rowan’s “Theorizing at Rowan” lecture series to encourage scholarly exchange among Rowan faculty, students and others around the country. The event welcomed Tamsin Kimoto, an assistant professor of philosophy and women, gender and sexuality studies at Goucher College in Baltimore, Maryland, for the lecture.

Kimoto’s original intention with this lecture was to “push back” on the “sexual prudeness of contemporary feminism” and develop a form of feminism that celebrates sex. However, Kimoto went on to state that the tragic shooting in Atlanta, Georgia on Tuesday, March 16, which killed eight people, including six Asian women, has “weighed heavily” on her. That, combined with the rising trend of violence against Asians within the U.S., resulted in Kimoto shifting the direction of her lecture to include a discussion that surrounded Asian American feminist history – including current events and crimes.

Kimoto began her lecture by discussing Congress’ passing of the Page Act of 1875 as part of a comprehensive review of immigration labor policies. One of the act’s key aspects was a ban on immigration for the purposes of sex work, which Kimoto said effectively became a “blanket ban” on immigration for women of East Asian descent.

“Asian women then enter into U.S. law as prostitutes,” Kimoto said, describing passages from the act, “and are therefore excluded from the possibility of even entering into the borders of the country.”

Kimoto went on to explain that, although some of the text sounds like a wide-ranging policy, its placement in the Page Act makes it clear that the main source of sex workers that the United States was concerned about were those coming from East Asia.

She highlighted words from President Ulysses S. Grant about the evils of “the importation of Chinese women,” which led to many Asian women being turned away at the border, as well as the use of the word “importation,” implying objects and not persons. This led to Asian women being denied personal agency under the law, due to essentially being labeled as objects.

Kimoto explained and critiqued carceral feminism – a form of feminism which focuses on increasing laws, regulations and prison sentences that deal with feminist issues. Kimoto described some of the strategies of carceral feminism, such as using “sex trafficking” to refer to all sex work, and collaborating with policy makers to pass stricter regulations around forms of consensual sex work, like pornography.

“Carceral feminism reinvests feminists’ energy in strengthening the same kind of state apparatuses that disproportionately impact women of color,” Kimoto said, “while simultaneously draining the same kinds of energy and resources from those parts that might offer whatever small improvements to those same lives.”

Kimoto added that carceral feminists have been enormously successful in advancing these kinds of agendas, explaining that she considers carceral feminism an example of “hygienic feminism,” which contributes to the issue of exclusion.

“Hygienic feminism focuses on purifying and protecting the category of woman from threats posed by kinds of women who do not fit a normalized picture of the properly feminist woman,” Kimoto said.

She stated that TERFs – trans exclusionary radical feminists – are another example of hygienic feminism, claiming that these types of radical feminists have turned feminism’s energy against transgender women and sex workers, given that they view both groups as images of “bad” women.

Kimoto concluded her lecture with her original focus, discussing the idea of “sluttiness,” a term which suggests the refusal and challenge of the logic of purity that hygienic feminist beliefs are built upon.

“Sluts take on the idea of being objectified, rather than [being] turned away from it. So, in a sense, choosing to be objectified – leaning into it,” she said. “And this is because sluts recognize that the subject-object relationship, on which the radical feminist position is premised, is ultimately a false dichotomy.”

Kimoto noted that when adding “class, race and queer narratives” to this picture, we get more complex notions as to what agency and objectification look like.

The event ended with a Q&A session, in which Kimoto discussed how stereotypes of Asian women seem to still exist, no matter how they present themselves, and provided examples of microaggressions often directed at the transgender community. According to Kimoto, the most subtle microaggressions are those that come off as compliments, such as, “I would never have guessed you were trans,” or “I’d still date you.”

Kimoto concluded by discussing her observations of the current climate of the United States and Asian women, in particular.

“We are at another one of these historical flashpoints where we can choose to reaffirm our status as the model minority, or make alternative spaces – alternative moves – and make them more broadly,” Kimoto said. “I see, right now, more energy than I’ve ever seen among Asian Americans to make this kind of move.”

For comments/questions about this story, email [email protected] or tweet @TheWhitOnline.

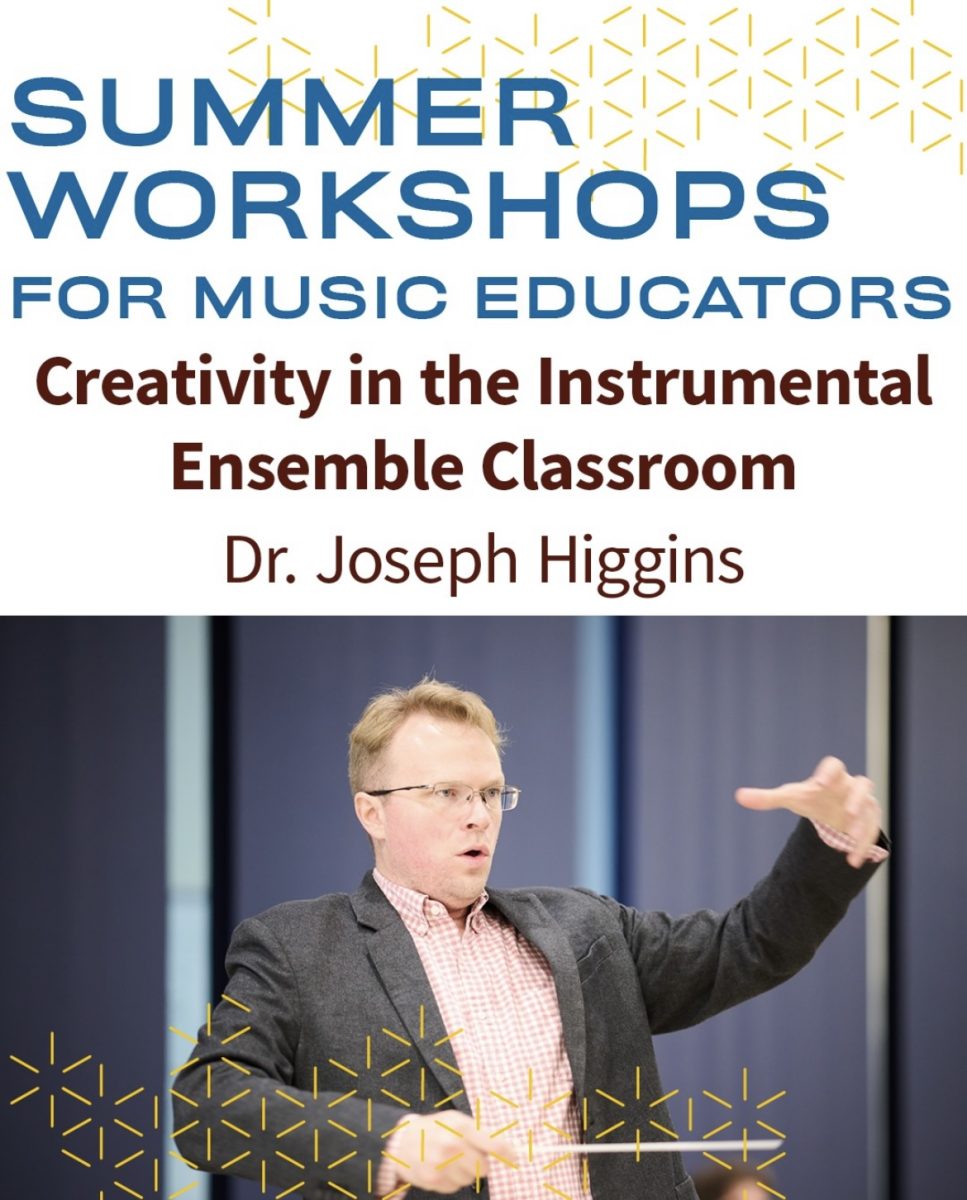

!["Working with [Dr. Lynch] is always a learning experience for me. She is a treasure,” said Thomas. - Staff Writer / Kacie Scibilia](https://thewhitonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/choir-1-1200x694.jpg)