What’s got the attention of just about every “cinephile” left and right is how “Parasite” took the Oscars by absolute storm. Its low budget, foreign language status coupled with estrangement from the traditional American formula were all barriers that many presumed would stop Bong Joon-ho’s film from getting nominations, much less winning them.

But in the end, the renowned South Korean director proved them all wrong, which is all for the better. “Parasite” echoes sentiments Bong represented in his lesser known, action-packed film “Snowpiercer,” which features literal class warfare in the context of an environmental catastrophe that has wiped out roughly 95% of humanity (If you haven’t seen it, go watch it. I’ll wait).

What makes “Parasite” stand out from Bong’s previous films, however, is how it folds its anti-capitalist messaging into the traditionally quiet suburbia, turning a narrative once somewhat distant in the minds of American cinephiles into one that could occur in our own backyard.

What makes “Parasite” a unique phenomenon is what it represents: a paradigm shift in the American bourgeois, a representation of at least some greater understanding of what is occurring in the vast chasm between the slums of Skid Row and the elites of Hollywood.

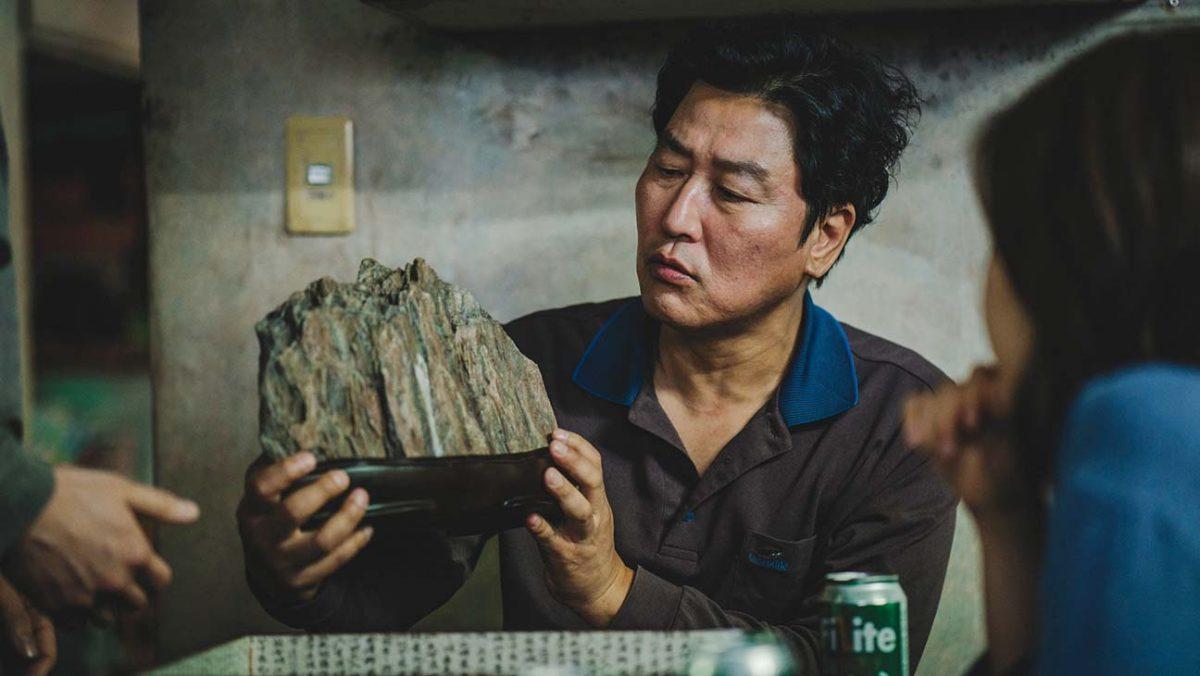

Within the film, Bong makes the contrasting existences of those who have wealth and those who lack it startlingly clear. The first family introduced in the film, the Kims, literally live in a basement and hop from low-paying job to low-paying job, hoping to be able to afford an education for their children and an escape from the equivalent of a sewer drain.

In stark contrast, the wealthy Park family live in the ever-familiar pleasant suburbia, a point Bong emphasizes with bright lighting until the final act of the film. This is made more poignant by the lighting of the Kims’ residence remaining almost always dark, if not outright dank in some aspects. The Park family wants for nothing and are carefree, their servants acting in the periphery of their endless whims if they are noticed at all.

What remains artfully subtle is how forceful the Park parents are about boundaries, being outright dismissive and sure about their “obvious” superiority over their servants and, eventually, over the Kims. However, this is all standard fare for many “con” movies. That is to say, none of these tropes is out of place in your standard heist or deception film a la “Oceans 13” or “Now You See Me.” What makes this film shatter narrative expectations is a spoiler. So if you haven’t seen it yet, stop here or at least be forewarned.

When the inhabitants of the basement discover the Kims’ scheme that usurped the prior servants, they threaten to shatter it before it comes to full fruition. But the Kims stop them, eventually resorting to violence to do so. All of this comes to a head on the day of a birthday party for the Parks’ son.

That afternoon, the son of the Kims takes a rock, signifying wealth, to finish the job his family started, resulting in a gory action montage emerging with little to no warning; “Careful Massacre of the Bourgeoisie” style (If you don’t know what that is, check it out, it’s on YouTube, but be warned, it is gory) while the Park family and their bourgeois friends look on in horror.

What “Parasite” shows is how capitalism compels workers to fight and even kill one another for the scraps left behind by the wealthy, who remain largely protected from the plight of those, sometimes literally, beneath them.

The success of “Parasite” illustrates how effectively this message was received. It illustrates that people are ready to see that workers must work together to get anything done. It illustrates that violence against each other is worthless. It illustrates that something doesn’t have to be American to be relevant to Americans.

It illustrates that the road to better things is never easy or short, but it is essential to progress toward equity and opportunity.

For questions/comments about this story, email [email protected] or tweet @TheWhitOnline.

!["Working with [Dr. Lynch] is always a learning experience for me. She is a treasure,” said Thomas. - Staff Writer / Kacie Scibilia](https://thewhitonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/choir-1-1200x694.jpg)