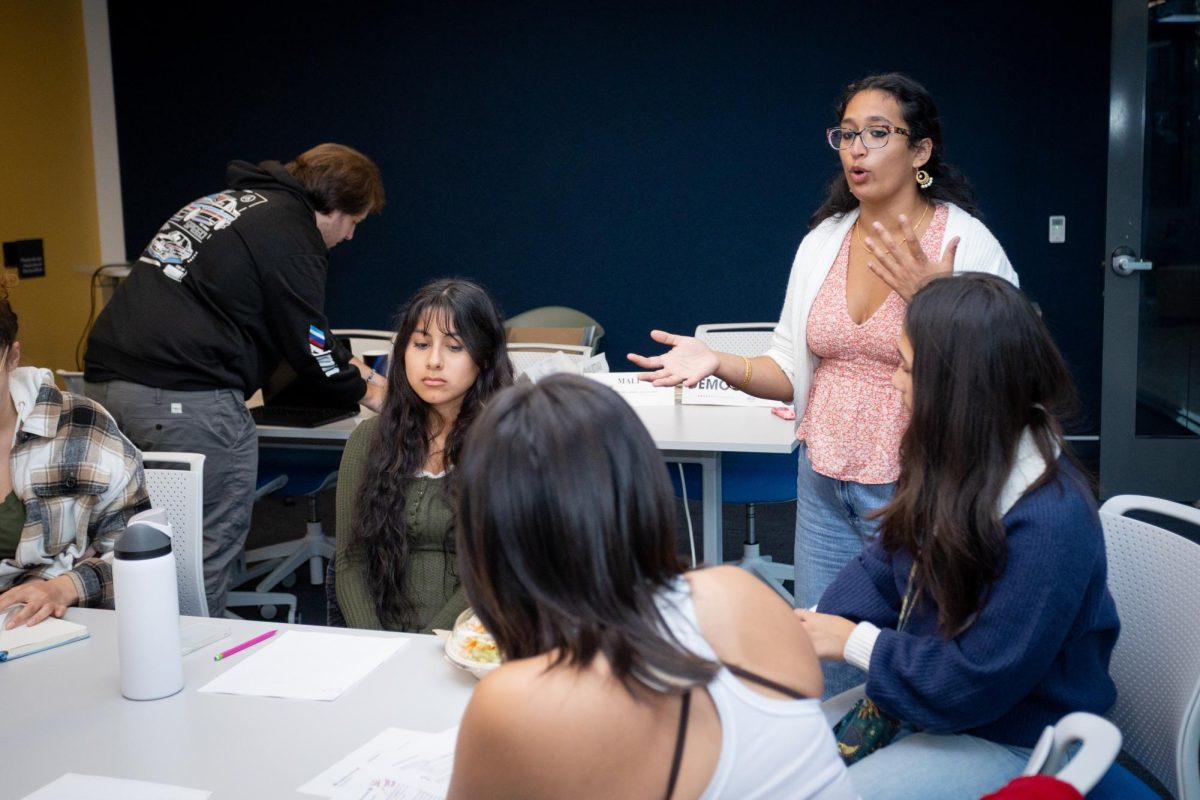

You don’t need to spend more than a minute on the Internet or watching the news to realize that people are very angry these days, arguably more so than ever before. Every minute of every day it seems there are thousands of people aggressively calling for “justice” or “change” or any number of other things.

Even without looking outward, we find plenty of anger in our own lives, be it our own, or from those we interact with within our daily lives. Everybody always seems to be mad about something like their classes, their job (or lack thereof), their friends, family, partners or broader issues such as the world, the government, the economy or the climate.

Some would say that this is a good thing. This increased anger shows that people are at least paying attention to serious social issues that demand it. Social awareness is a good thing. However, pragmatist that I am, I feel compelled to analyze the potential negative impact of this new wave of anger and what we can do about it.

As I see it, there are two kinds of anger: righteous and unrighteous. Righteous anger, I call passion. It is a desire for justice, motivated by sympathy that seeks to build and maintain peace. Unrighteous anger I call wrath. It is a desire for vengeance, motivated by hatred, that seeks personal compensation at a harmful cost to another.

Passion is the justifiable feeling of dissatisfaction with an unfair situation, and the willingness to change it into something better. Passion, as I’ve defined it, is the engine of real and enduring social change because it is based in reality and seeks to transform reality. Passion is a good thing.

But wrath, however, is not. Wrath is the personal vendetta we have against something (or someone) for their thoughts, words, or actions (real or perceived) against us. When our pride is damaged, say, by an insult or feelings of jealousy, wrath is the “restoring force;” it seeks equal injury against the supposedly responsible party, in the false belief that it will fix the damage.

Whenever we experience anger, it is likely a combination of both passion and wrath. Rarely is it all of one or the other? Furthermore, it is difficult to know which is which without careful self-evaluation of our feelings. Needless to say, careful self-evaluation is difficult when we’re angry.

What’s far easier is to simply act impulsively in a way that we think will make us not be angry anymore, no matter the consequences. But whether our anger is passionate or wrathful, impulsive action never resolves the issue, more often than not making it far worse for ourselves and anyone involved.

On a small scale, personal disagreements can escalate into violent and even lethal fights. On a larger scale, marches and political rallies can escalate into riots that are as destructive and horrifying as natural disasters.

We must never let our emotions overcome our reason, lest chaos and destruction follow. To that end, it is imperative that we learn to properly process anger.

When you feel angry, stop. Don’t do anything. Go somewhere quiet and breathe. Consider why you are angry. Has any real injustice been done? Or was it merely a personal offense that you can probably let slide with little consequences? If it was a genuine injustice, can you do anything about it? Should you, given your resources and understanding of the situation? Will retaliating just make the situation worse, or is it worth a try?

These are important questions because they reflect how we shape the world around us. In an era where we are often expected, if not encouraged, to act impulsively, to “do what feels right,” it can be excessively difficult to nurture this kind of mindful hesitation. But by swallowing our pride and taking the time to analyze why we’re angry and how to best respond to it, rather than simply swinging blind, hoping to hit something, we don’t get as angry.

Instead, we get contemplative. And contemplation is the beginning of peace.

For comments/questions about this story tweet @TheWhitOnline or email [email protected].