I never even thought about being a doctor as a kid. I didn’t quite walk right, I couldn’t stand for too long and my hands would often feel sharp pains that caused me to drop whatever I was holding. As a kid, I was labeled clumsy and “artistic” (which is what parents say after their kid keeps getting hurt while trying to play soccer). As an adult, I found out that I wasn’t “clumsy,” I was disabled. So I never stood a chance at being a doctor.

In the United States, 26% of the population has a disability. But in the medical community, disabled people make up just 3.1% of the physician population. These numbers show a distinct lack of proportional representation for one of the United States’ largest minorities, one that has consistently fought for inclusion and equal rights but is still plagued by the stereotypes surrounding disability.

While the narrative surrounding medical students and physicians is that of people who are independent and capable of providing care, however, disabled people are often considered as dependent on others and in need of care. This contradiction inherently excludes disabled people from the perceived environment of medical communities.

It wasn’t that I thought I wouldn’t be a good doctor. I had high grades in math and sciences and took AP Biology in high school. But I still never considered the medical field to be an option available to me. It wasn’t a place that I could fit into. Sure, I was invested in my academics and — after several hospital stays, exploratory procedures and countless tests — had a fairly robust understanding of the day-to-day medical process, but how could I provide medical care to others when I was in need of so much of it myself?

Disabled people not only deserve to be in these spaces, but they are also invaluable resources. So many of the disabled community’s frustrations with doctors and doctors’ visits come from an inherent lack of understanding about disability and how it affects our day-to-day life. They don’t believe us when it comes to our pain or levels of function unless it “impacts our ability to work.” Having a disabled physician would eliminate this barrier for disabled individuals in health care. Additionally, it would allow disabled physicians to educate fellow members of the medical community on the realities of disabled people.

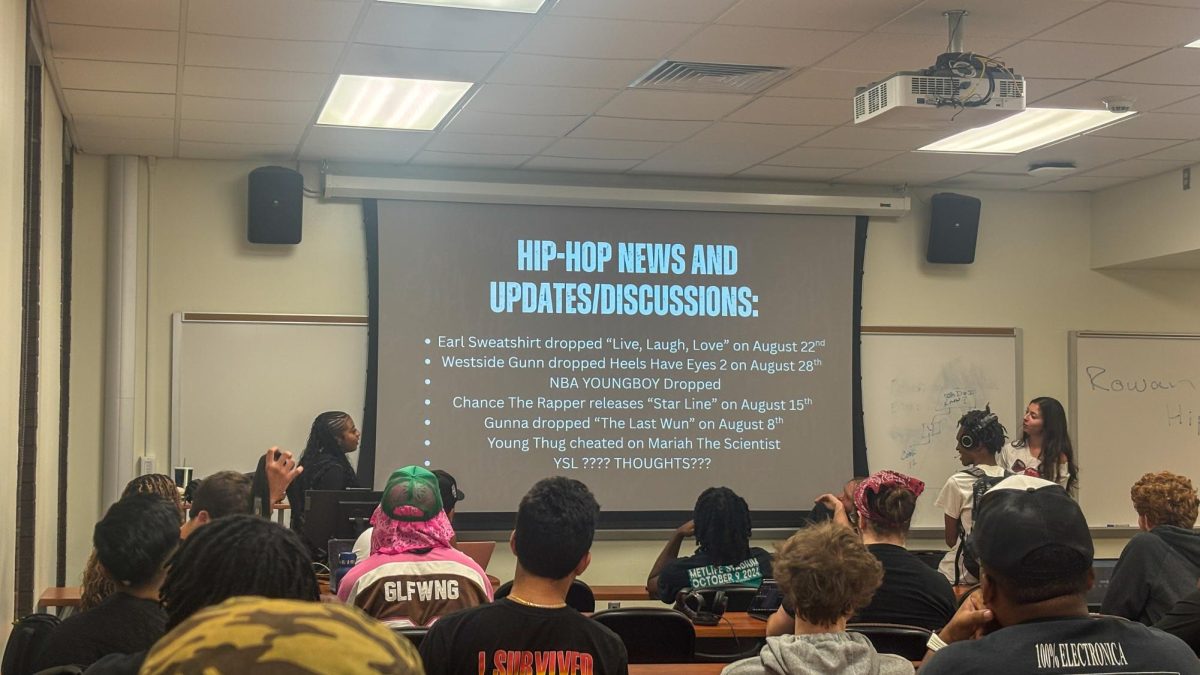

To bring more disabled individuals into the medical field, medical schools need to be proactive in encouraging and accepting disabled candidates. At Rowan University medical schools, similar programs are in place to encourage medical education among people of color and people from Indigenous backgrounds. These pipeline programs are meant to inspire students who may not be as encouraged as their peers to pursue medicine. With the overwhelming success that they have, there is no reason for Rowan University medical schools not to create one targeting disabled individuals.

These programs just need to start small. The most immediate and effective beginning to a pipeline program for the disabled community is to introduce a scholarship meant for physically and intellectually disabled individuals to obtain and put towards their medical degree. Even something relatively small in the scheme of tuition costs, such as $3,000 or $5,000, can make a massive impact on their educational costs.

Even if this scholarship isn’t one that students are automatically considered for, creating an essay barrier asking students to discuss the impacts that their disability has had on their educational career not only provides them with an outlet to discuss how their disability has led to their current place in life but also show to medical school admissions officers how disabled people have overcame and embraced their disability to become the medical-focused people they are today.

Beyond the impact on educational costs, a scholarship such as this shows disabled individuals that they are wanted in this field. The physical nature of the medical field and the emphasis placed on a doctor’s physical capabilities can be extremely intimidating — often discouraging — to disabled individuals considering this career. So often, disabled people are made to feel unwanted and incapable of pursuing this career but seeing that there is a pipeline program dedicated to their inclusion can be the sign people need to join the medical field.

After spending four years in physical therapy, I idolized the healthcare professionals who took care of me and taught me how to understand my body as a disabled person. However, when I looked at them interacting with patients and partaking in the physical aspects of their job, I could never see myself in their shoes. Disabled adults need to be prioritized in healthcare so that the next time a disabled child asks themselves what they want to be when they grow up, the sky’s the limit.

For comments/questions about this story, email [email protected] or tweet @TheWhitOnline