No matter when or why, the blunt and hard truth of the world is that everyone will die. It’s a fact that most people don’t like talking about, or even thinking about if they can help it. It’s considered uncouth to bring up in polite conversation, but it makes it no less true.

Eventually, the time will come when all living things will pass on. And when that time comes, decisions have to be made about what to do with the remains of the deceased person. For most Americans, there are typically two options for remains that are considered traditional and acceptable: burial in a cemetery or cremation. In recent years though, options have been expanding.

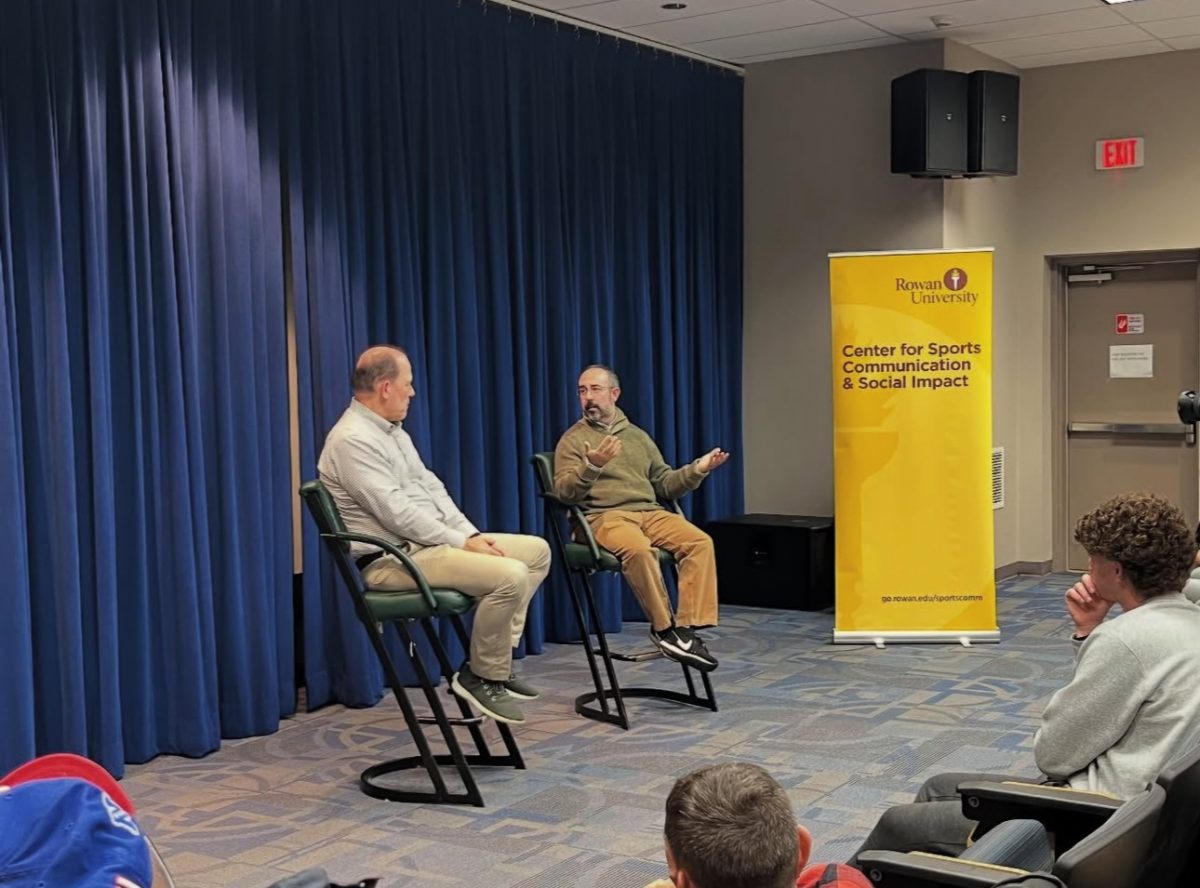

Rowan University recently held a talk on this exact subject. David L Baylis Ph.D., an assistant professor at the Center for Integrative Studies in the College of Social Science at Michigan State University hosted “From Garden Cemeteries to Mushroom Suits: Green(ing) Death in the United States,” focusing on the various ways that are now available to make death more healthy and safe for the environment.

“It’s a topic that sometimes causes people to feel some discomfort… I teach an entire class about green death care. Initially, students are in particular really trepidatious to have conversations about it, but they tend to open up really quickly,” said Baylis as part of his opening remarks to the crowd.

From there, Baylis got into his history of spooky childhood interests as well as his own anxiety around death, saying that he believes these to be linked. He then went on to ask how many in the audience had thought about their final dispositions, to which most people in the room raised their hands.

“Given the fact that you’re attending this talk, that’s not entirely surprising to me. And it turns out I actually run into this quite a bit. Even with my grad students in large classes, a lot of them actually had thought about it. They maybe don’t talk about it. But they have at least thought,” said Baylis.

However, when asked how many in the audience had actually put something in place, only a few were able to say they had. After the introductory question, Baylis got into the discussion of the ecological effects of modern funeral practices, as well as what he called the low-tech alternatives versus the high-tech ones.

Both burial and cremation bring with them fossil fuel emissions, chemical pollution, and resource use as well, meaning neither is particularly eco-friendly.

For burials, the issues are numerous in ways most people would be able to suspect. The land use, chemical leakage and pollution from embalmed bodies, use of machinery to dig the graves and the materials used in coffins, caskets, and headstones are all fairly obvious and prominent issues in burials.

The actual numbers behind these effects are more surprising. Annually, traditional American burials use 30 million board feet of hardwood, 2700 tons of copper and bronze, 104,272 tons of steel, and 1,636,000 tons of concrete. This amount of concrete is necessary to keep the ground flat, to allow for easy upkeep of cemetery grounds throughout the year.

With the number of resources used in traditional cemetery burials, cremation seems like a better option, until the emissions and resources are taken into account on that one. Each cremation releases approximately 600 pounds of carbon dioxide, as well as polluting the air with mercury. In addition to this, many who are cremated still have their bodies embalmed for a viewing before the cremation takes place.

While the two main ways people choose their final dispositions are not healthy for the environment, and in some cases, for the living people around the area, in recent years a number of green alternatives have come to be discussed more broadly.

One of the most standard “green death” options is what is called a green burial, designated as one of the low-tech options by Baylis.

This process is similar to how burials have been performed before the advent of modern technology. The unembalmed body is put into a casket or shroud made of biodegradable materials, then lowered into a grave that has been opened manually with shovels rather than with machinery. Families usually participate in this process as well.

Cemeteries that allow such a process are usually called garden cemeteries, and they take great measures to ensure that the natural landscape is disrupted as little as possible. Some won’t even allow headstones, though others will as long as it is a natural stone that is native to the surrounding area.

One such cemetery is located in South Jersey, called Steelmantown Cemetery. Ed Bixby is the founder.

“It’s like any other traditional cemetery. The major difference, obviously, is it’s a woodland burial preserve. So, the formal status is obviously what we are used to. But the daily operations really are to be taking care of the trail system, interring people out in nature in the woods. It’s less time-consuming. Not much to really do in comparison to like a traditional facility that has a lot of daily operations,” said Bixby.

The deceased usually chooses to be buried in Steelmantown ahead of time, but families can also choose it for their loved ones if they feel it’s what they would have wanted.

Steelmantown allows headstones so long as they are native to the mid-Atlantic and not polished or set in concrete, though they can be painted or engraved. Living grave markers like trees and shrubs are also allowed.

These green burials can do more than just help the environment. A famous quote, attributed to several different authors over the years, reads “Funerals aren’t for the dead. They’re for the living.”

In this vein, many in the death care industry say that green burials help families in the healing process.

“[For] individuals who are part of the process, it’s a very cathartic experience. Being hands-on caring for your loved one and then that final act of kindness to bestow upon them, it’s kind of life-changing in the sense that people will talk about death. People like to be part of that process in the traditional sense of the word, but when they are out of nature, and they’re actually physically being part of it, it kind of changes their perspective. The event itself becomes more of a memorable celebration of a life that was lived and it becomes far less scary,” said Bixby.

Though green burials aren’t the most common currently, they are gaining popularity. Almost 54% of Americans report that they are considering a green burial and 72% of cemeteries have reported an uptick in interest and demand for the practice as well.

Steelmantown also offers water options for burial, which involves adding cremated remains to special concrete structures that are specifically designed to foster marine life. The reef balls help to restore reef systems and provide habitats for marine life, restore fish biomass, and aid in the regeneration of coral.

Green burials are the most traditional option, and also the one that is most likely to be easily accessible, but it’s not the only way to make a person’s death more eco-friendly.

Instead of traditional cremation, another option is alkaline hydrolysis, also called aquamation, water cremation, or bio cremation. Considered by Baylis to be a more “high tech” option, this process, which is currently mostly used to dispose of livestock, uses a pressurized vessel filled with water and potassium hydroxide to break the remains down to their chemical components. At the end of the process, the body is left as an inert green-brown liquid and the remains of bones. What is left of the bones can be crushed into white ash and returned to the family, while the liquid that is left over gets run through the local wastewater system.

This process is much more controversial than green burial, as in the eyes of the law, if something was once human remains, it is always human remains, meaning that the idea of running the liquid remains through the wastewater system raises concerns around ethics and morality of the process.

All of these concerns are why the process is largely illegal. Regulatory bodies also worry about the water usage it requires during droughts.

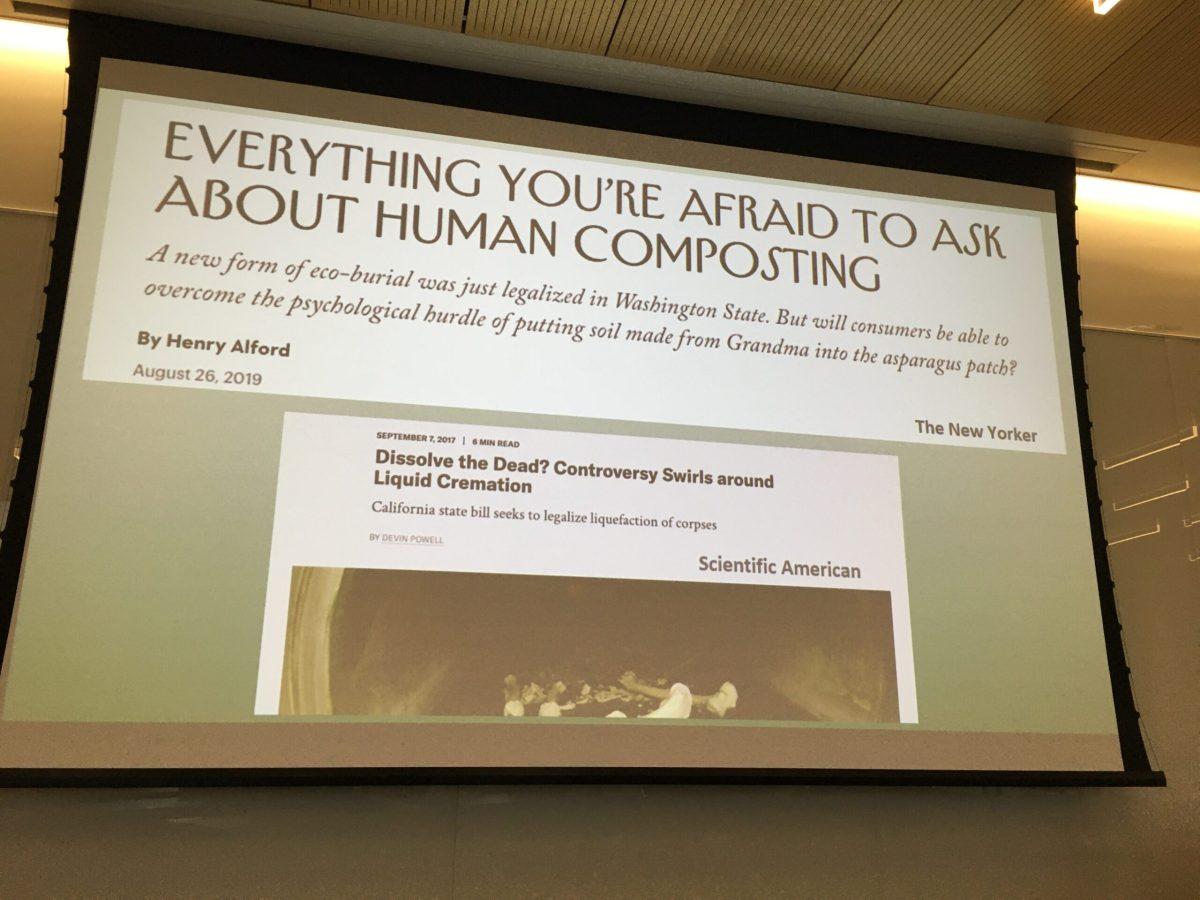

Another option that has been both gaining popularity and garnering controversy in recent years is human composting.

Similar to aquamation, human composting involves putting the body into a vessel to break down the body, though this one relies on the use of microbes from natural materials to break down the body over the course of five to seven weeks. This turns the body into about one cubic yard of soil amendment, which can then be used by surviving loved ones to plant a memorial tree or other form of living memorial.

Human composting company Recompose is working to get the practice to be more widely accepted and legal in more areas, as it is currently only legal in seven states; Washington, Colorado, Oregon, Vermont, California, New York, and Nevada. An additional 24 states are considering legislation on the issue.

A lesser-known but completely legal option for green burial is a mushroom suit, which actor Luke Perry was buried in upon his passing. The main company that handles this kind of burial is Coeio, and the process works by putting the body into a suit made of organic cotton with mushroom spores. This type of burial helps to break down the body so that it nourishes the plant life around it.

Though it is legal, some cemeteries will not allow it as an option, as they require traditional caskets, so that will have to be kept in mind for all who are interested in their particular method of burial.

Another option is a tree pod, where the cremated remains are placed into a large soil pod with a small tree or sapling that will grow large with the nourishment of the body.

However, Baylis says that this method raises concerns, as some forms still involve cremation, which has high emissions of carbon dioxide related to it, and cremated remains have been known to actually harm plants. For intact bodies, high-nutrient pods are still unavailable for burial, and this form of final disposition only currently exists in concept.

These cremation pods are legal, though they can be difficult to access, as space, cost and an area’s regulations can all be mitigating factors in having this kind of cremation and burial.

There are other forms of green burial around the world, though several of these methods are highly unlikely to ever be legally adopted in the United States.

Baylis spoke of his personal interest in vultures, showing the audience his tattoo of a bearded vulture, a type of bird that evolved to survive on a diet that primarily consisted of bones. This led Baylis to say that, though it is highly unlikely to ever be legally available in the US, he would be very interested in a traditional Tibetan sky burial, which consists of remains being left on a designated platform exposed to the elements, usually in the mountains. The body is then allowed to be eaten by vultures and other scavengers, symbolizing the circle of life and returning the body to nature.

Baylis also discussed his fear and general aversion to any type of burial, not liking the idea of being underground. While any kind of sky burial will likely never be legal here, Baylis’ second choice would be aquamation, as it doesn’t involve being put underground in any way.

For comments/questions about this story DM us on Instagram @thewhitatrowan or email [email protected]