Just a few blocks from the boulevard at 301 High Street is Rowan Art Gallery and Museum. On Jan. 27, they opened their latest exhibition, “Carrying On: Black Panther Party Artists Continue the Legacy.”

This exhibit, curated by Colette Gaiter, features the work of four artists whose lives intersected through the Black Panther Party and specifically their work for The Black Panther newspaper.

Gaiter is a Professor Emerita from the University of Delaware and an artist herself, though now she primarily operates as a writer. Gaiter has dedicated much of her life’s work to the study of Emory Douglas, the first Revolution Artist of the Black Panther Party, and later served as the Minister of Culture from 1967 to the dissolution of the party.

Gaiter says that Mary Salvante, Director and Chief Curator of Rowan University’s Art Gallery and Museum, had initially only asked her to curate an exhibition of Emory Douglas’ work. He still features prominently in the exhibit, with a wall of the gallery displaying works of his from 1969 through the present in full view.

The choice to include the other three artists: Gayle Asali Dickson, Akinsanya Kambon, and Malik Edwards, was fueled by her discovery of their work in the Black Panther Party.

Gaiter says that one reason she chose to include them was through research.

“It was probably a combination of things. One was just research, just by looking at a lot of newspapers and they [the artists] all signed their work, which, I don’t know if Emory Douglas encouraged that, but that is so good because so many artists don’t or are not allowed to,” said Gaiter.

She also says that she spoke with Douglas and asked him who else had worked with him in the Black Panther Party.

And so, the exhibit is divided into sections for each of the four artists, with walls segmenting the gallery, providing sections for each person’s works. The first thing a visitor may notice, however, is the large-scale timeline on the back wall of the gallery.

The timeline travels from 1619 when the first slaves arrived in Port Comfort, [Hampton] Virginia, to the civil rights movement and creation of the Black Panther Party, and lastly, the dissolution of the Black Panther Party in the 80s.

“Carrying On” is deeply tied to Black history, and as such it was very important to Gaiter that there be a timeline showcasing that.

“I would ask everybody who comes to read the timeline and read the artist’s statements because there are so many more stories than what is visible from just looking at the work. It all needs to be contextualized,” said Gaiter.

Gaiter also sought to use this exhibit as a way to correct misconceptions about the Black Panther Party.

“[…] most people think they were violent and that their only goal was to overthrow the US government. Now, you could say this about the Jan. 6 rioters, but the Black Panther Party never tried to overthrow the US government,” said Gaiter.

She describes how in the 70s, the Black Panther Party shifted from an organization focused purely on defense, into one of survival.

“They were called survival programs, helping people get food, health care, education, legal services, medical services, et cetera,” said Gaiter.

The timeline, and artist’s statements which are provided on the walls next to their work, and also within guides provided at the entrance to the gallery, clarify misconceptions and provide the context Gaiter encourages visitors to spend time with.

Gallery guides and the text on the walls of the gallery are designed in part by Gallery Coordinator Kristin Qualls, as well as videos playing throughout the gallery which have accessibility features such as headphones and captions.

As for the exhibit itself, the artwork is striking and spans the start of the Black Panther Party to the present.

Gayle Dickson’s earlier work features pen and ink drawings of women and children which were printed in The Black Panther newspaper.

Her recent work, displayed beside these reproductions and drawings, has similar themes of African American women and protest and history, though she has since transitioned to a new medium of paint and canvas. Her latest creations feature bright colors and unique textures. Postcard prints have the same motifs as her older work but are simplified through watercolor and marker.

Akinsanya Kambon and Malik Edwards’ work from their time in the Black Panther party is similar in the sense that the two of them had just finished serving in the Vietnam War. Gaiter points out that this reflects how the Black Panther Party saw themselves as an international movement, through their involvement with international liberation movements.

Two of Kambon’s paintings from the year 2000 are displayed in this exhibit, one of a Vietnamese woman standing in a plot of land while another person plants crops behind her, and the other of two soldiers in a similar plot of land, running.

Across from these paintings, are his most recent works, three sculptures of clay and bronze, which, per the guide, “visualize narratives of the Black diaspora.”

Among Malik Edwards’ section of the exhibit, are two pieces from 1983, one titled “East Meets West,” and the other entitled “Endangered.”

“East Meets West” encapsulates his surrealist style, with Eastern motifs, and is a rendering of two people, presumably one from the West and one from the East.

“Endangered” is a much more literal work and is a lithograph poster featuring an atomic explosion in the background as two migratory birds fly past in the foreground, with the words “ENDANGERED, support the nuclear weapons freeze” in the text at the bottom.

Emory Douglas’ work is equally evocative, spanning across an entire wall of the gallery. One of his works, “All Power to the People: Paperboy,” has been remixed three times from 2015 to 2021. It’s a drawing of a Black child holding up a newspaper that says, “All Power to the people.”

The remixing espouses his message of always recognizing the oppression of others, in a way saying that his work is never done.

His other works include inkjet pieces on gang violence, police brutality, and slavery. In line with international themes, two embroidered blankets he created in partnership with the Zapatista Family Morelia in Chiapas, Mexico, hang on the wall among the rest of his work.

As the title of the exhibit would suggest, “Carrying On” is a unique look into each lifetime of these artists, and features works ranging from Black liberation to wealth inequality to war as well as peace.

There are a few overarching themes that tie the exhibit together. Gaiter says one is liberation. and another is “belief in something bigger than yourself.”

“I think that all of the artists in their own way are thinking about ancestors, you know, and thinking about who came before them,” said Gaiter.

This is evident in the usage of Adinkra symbols across various works in the gallery, which symbolize various attributes, the inclusion of African figures, or even the choice to use African rituals in the creation of the artwork itself.

In creating this exhibition, Gaiter met with the artists and discussed their work, learning more about their histories. She also utilized the internet to find more niche creations that maybe even the artists themselves had forgotten.

After acquiring the rights to reproduce and display some works, such as art featured in The Black Panther newspaper, she partnered with the people of Rowan Art Gallery and Museum to bring all the works together into a cohesive exhibit.

On Salvante’s end, putting together this exhibit from start to finish began with reaching out to Gaiter, who she had worked with before on smaller projects.

“We had an exhibition with Jamea Richmond-Edwards, another Black artist, and I invited Colette to write an essay for her catalog, which she did. And so fast forward, we were talking and I knew that she had been doing a lot of research on Emory Douglas […] and I saw that this would perhaps be a great opportunity to do a show on Black Panther artists, so I invited her to curate the show,” said Salvante.

“Carrying On: Black Panther Party Artists Continue the Legacy” will run until March 15, 2025. Rowan Art Gallery and Museum is free to visit and is open to the public from 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. on Monday through Friday, and 11:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. on Saturdays.

For comments/questions about this story DM us on Instagram @thewhitatrowan or email [email protected]

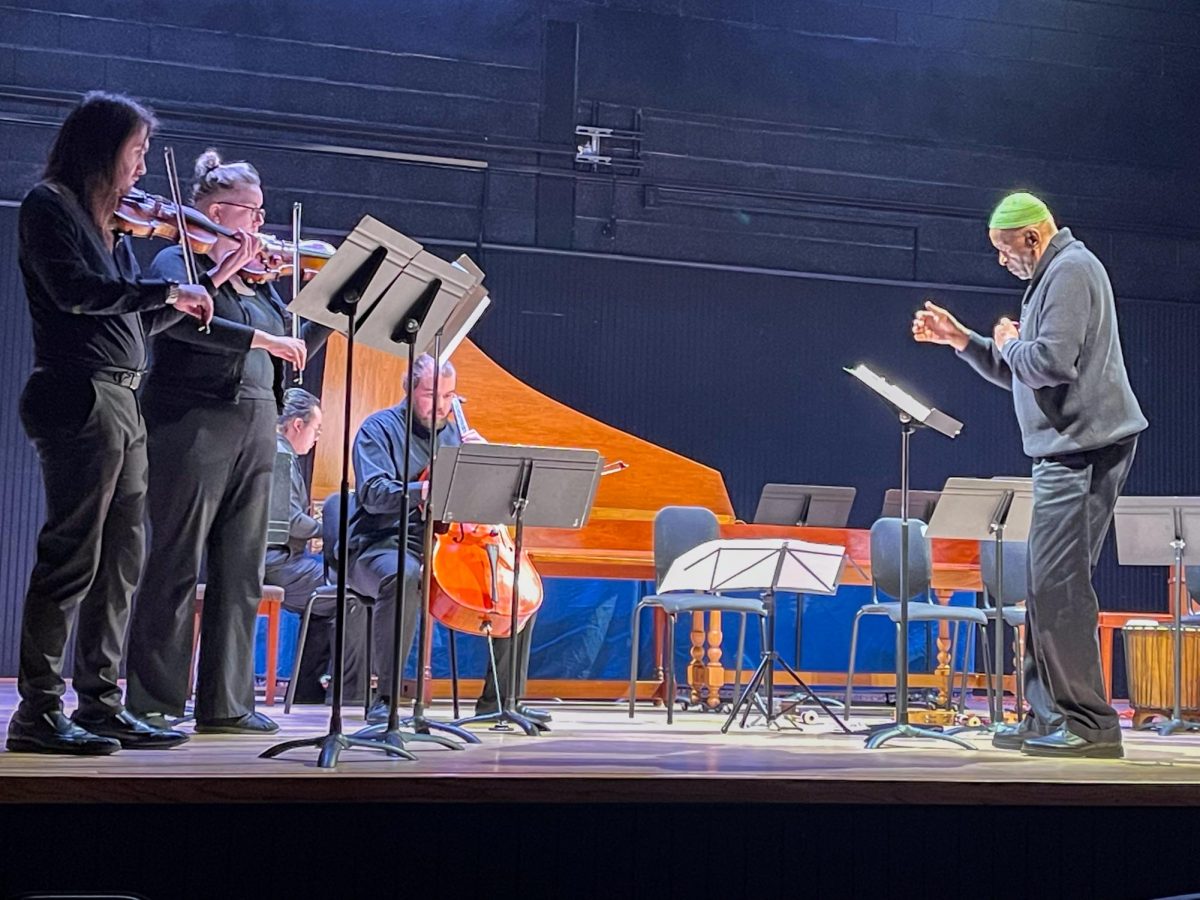

!["Working with [Dr. Lynch] is always a learning experience for me. She is a treasure,” said Thomas. - Staff Writer / Kacie Scibilia](https://thewhitonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/choir-1-1200x694.jpg)