On Wednesday, March 26, the Rowan Center for the Study of the Holocaust, Genocide, and Human Rights hosted a student-led discussion on China’s genocide of Uyghur Muslims in the Xinjiang region. The talk was focused on why something labeled as a genocide has disappeared from the media.

“When you talk about Bosnia, Rwanda, Americans were watching that unfold on the news every single day it was happening,” said Angelina Witting, a senior history major and co-president of Rowan’s Center for Holocaust, Genocide, and Human Rights. “We were aware then. We’re not aware now.”

The Uyghur Genocide represents a sensitive human rights problem. The Uyghur are an ethnic group of about 11 million Turkish Muslims who were centuries-long natives of what is now the Xinjiang region of China. The Xinjiang government has imprisoned between 800,000 and two million Uyghur Muslims since 2017 when satellite images of buildings resembling open-air prisons were found in Xinjiang. Uyghur Muslims in the area are also subjected to strong state surveillance, religious limitations, and second-class citizenship. Any violations of these or other restrictions could result in being sentenced to one of the region’s prisons that the Chinese government labels as reeducation camps.

The talk began with a Vice documentary about two journalists pretending to be tourists who entered Xinjiang to investigate the government’s treatment of the Uyghur. The two encountered and interviewed Xinjiang Uyghurs who were too afraid of scrutiny and imprisonment to talk openly, formerly imprisoned Uyghur who recounted the cruelties they faced in the prison camps and Xinjiang Chinese who nonchalantly claimed the Uyghur Muslims were terrorists. At several points the two were approached by Xinjiang police, told they were not allowed to conduct any interviews, and were forced to delete interview footage from their camera. The journalists also searched for and recorded the schools where young children of Uyghur prisoners are taken and raised as wards of the state. The documentary showed that outside journalism in Xinjiang is made difficult by China’s restrictive government.

The talk then continued into a discussion on the other reasons why the Uyghur genocide is not covered by the news or media. The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted American media and news, with any coverage of the Uyghur obscured by evidence showing the virus originated from a lab in Wuhan, China. The controversies and lasting impacts of the 2020 election demanded the attention of news media, shifting media focus further towards mostly domestic coverage.

“America is now beginning to lean towards isolationism. Do they want people to know about this? Probably not,” said Sara Farris, a junior history major.

Another reason is that the Uyghur are Muslim, a group that has been targeted by American policies as a result of suspicion after the September 11, 2001 attacks by the terrorist group al-Qaeda. This can even be seen in the documentary, where Xinjiang citizens and officials label the Uyghur Muslims as terrorists.

“It’s probably because of the targeted group. The United States is historically Islamophobic. I think if the targets were a different group, maybe things would be different,” Witting said.

However, the discussion highlighted that gaps in American media are not solely responsible. The Uyghur Genocide’s status as a cultural genocide is also a potential reason why it is seen as less important. Unlike the Rwandan and Bosnian genocides that captured the world’s attention by inflicting widespread casualties, the Chinese government intends to systematically eliminate the Uyghurs’ cultural identity within Xinjiang. Even if the Uyghur Genocide were brought to light on an international stage, China’s status as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council grants them a measure of immunity from human rights sanctions that their treatment of the Uyghur could impose.

While the Uyghur Genocide seems an impossible problem to meaningfully deal with, there are still actions that Americans and Rowan students can take to help spread awareness.

“Ask other people, see if they know or spread their own knowledge, and advocate for it in their own way. Because now social media is a big way for activism to take charge,” Farris said.

When information can travel the globe in an instant, that information can potentially be critical to the lives of millions of Uyghur, even if those lives are difficult to see with our own eyes.

For comments/questions about this story DM us on Instagram @thewhitatrowan or email [email protected]

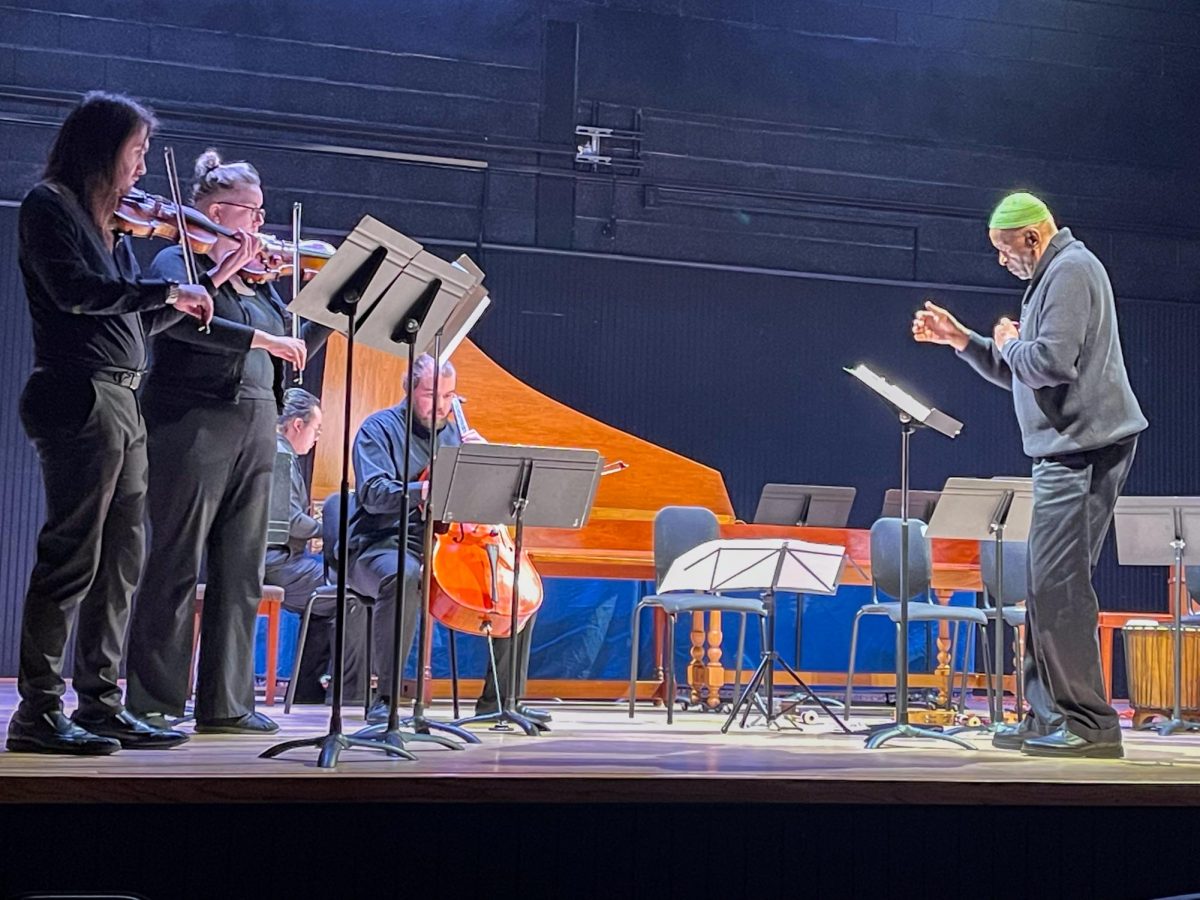

!["Working with [Dr. Lynch] is always a learning experience for me. She is a treasure,” said Thomas. - Staff Writer / Kacie Scibilia](https://thewhitonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/choir-1-1200x694.jpg)