With the rise of the internet, conspiracy theories pervade everything from everyday conversation to whole political movements. In 2020 and 2024, conspiracy theories like Q-Anon spread like wildfire on the American right wing. 20% of Americans believe COVID-19 vaccines microchip Americans, and another 54% of Americans believe that JFK’s assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald, did not act alone.

Despite this, overall, college students believe in conspiracy theories less than the average American, mostly due to a stronger education. Is Rowan University any different?

On average, not really. Among Rowan students, such theories don’t appear too common, though they’re not nonexistent.

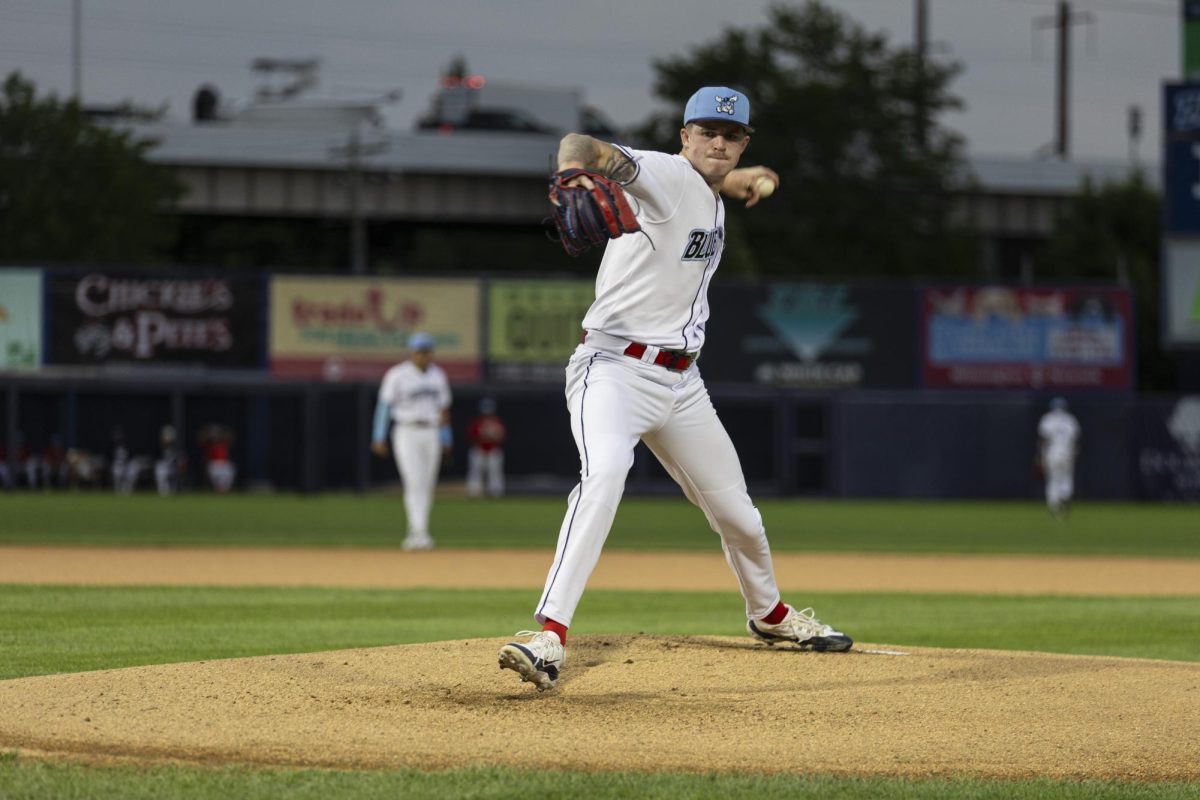

Gracie Tomeipar, a junior majoring in liberal sciences, is skeptical but finds them fun, citing a belief in the “mothman,” a winged creature from West Virginian folklore thought to be a bad omen.

“I don’t actually believe him, but I choose to believe him…the mothman,” Tomeipar said.

To Tomeipar, logic is more important, citing limited evidence in most cases.

“I think the world is weird enough that we don’t really need conspiracy theories … some of them have way too many statistical problems … I’m somebody who likes to have empirical evidence,” Tomeipar said.

Another student, Daniel Eang, a junior majoring in computer sciences, like Tomeipar, considers most of them unreasonable, but still finds one convincing: aliens.

“My mom did say that she saw some video about UFOs online. I mean, it does exist, space outside of the Solar System … So I do believe in those kinds of alien conspiracies,” Eang said.

Jaedon Angelus, a junior majoring in biology, says he enjoys reading about them, but doesn’t believe in any. He simply remains open-minded.

“I wouldn’t say I necessarily believe any of them, but I enjoy reading about them. I’m talking, getting my own perspective on conspiracy theories instead of just believing what I read,” Angelus said.

To him, conspiracy theories aren’t very reliable, since many begin in internet echo chambers and change as they’re repeated without sufficient pushback.

“I just try not to trust other people … A lot of information just gets put out there, it’s really reverberated in echo chambers and everything,” Angelus said.

Travis Reese, a sophomore majoring in psychology, doesn’t believe in any, although he didn’t specify any reason why not.

“I don’t think I have a particular reason. I just don’t,” Reese said.

Like Reese, Hani Patel, a junior majoring in computer science, doesn’t feel they can be substantiated. To her, this means they likely aren’t true.

“I just don’t believe them. If you can’t see it, it’s not real. That’s what I think,” Patel said.

Among those interviewed, some of whom refused to be quoted, few appeared to believe in any popular conspiracy theories, like Roswell or the aforementioned JFK plot.

As to why, on average, students in higher education have greater analytical tools, exposure to different viewpoints, and tend not to attribute intentionality to otherwise random events.

A lack of critical thinking skills and echo chambers reinforce conspiratorial ideas, all of which higher education combats, according to a research paper in the National Library of Medicine.

Despite this, many students, like Tomeipar and Eang, remain open-minded and engage with such theories, mostly for fun or out of personal interest.

For comments/questions about this story, DM us on Instagram @thewhitatrowan or email [email protected]