Editor’s note: This article has been updated for accuracy. The previous information within the article indicated that Mary Salvante was the “gallery and exhibitions program director.” This is incorrect. It has been updated to say that Mary Salvante is the Director and Chief Curator at Rowan University Art Gallery and Museum.

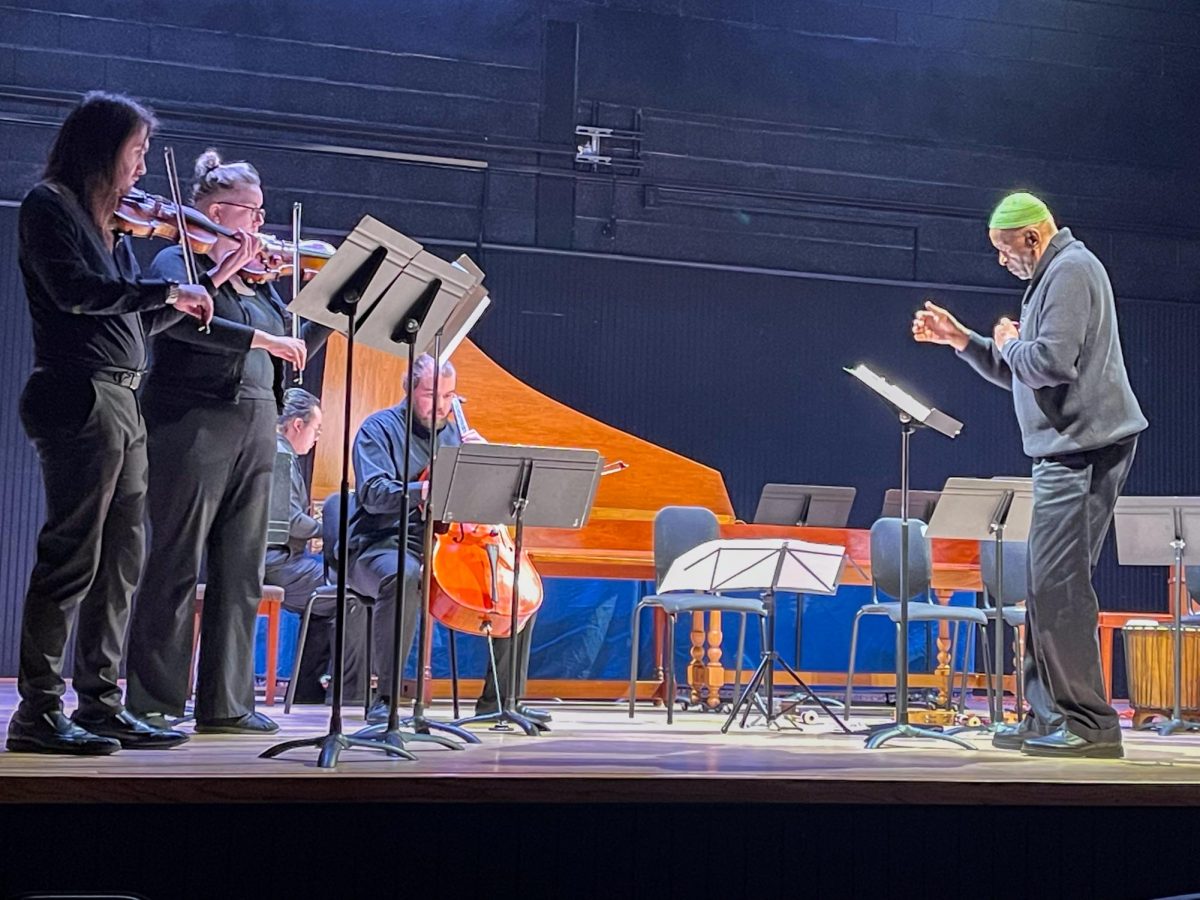

An evening in Rowan University Art Gallery and Museum filled the hall with mingling guests, jazz, and the haunting past of racial injustice.

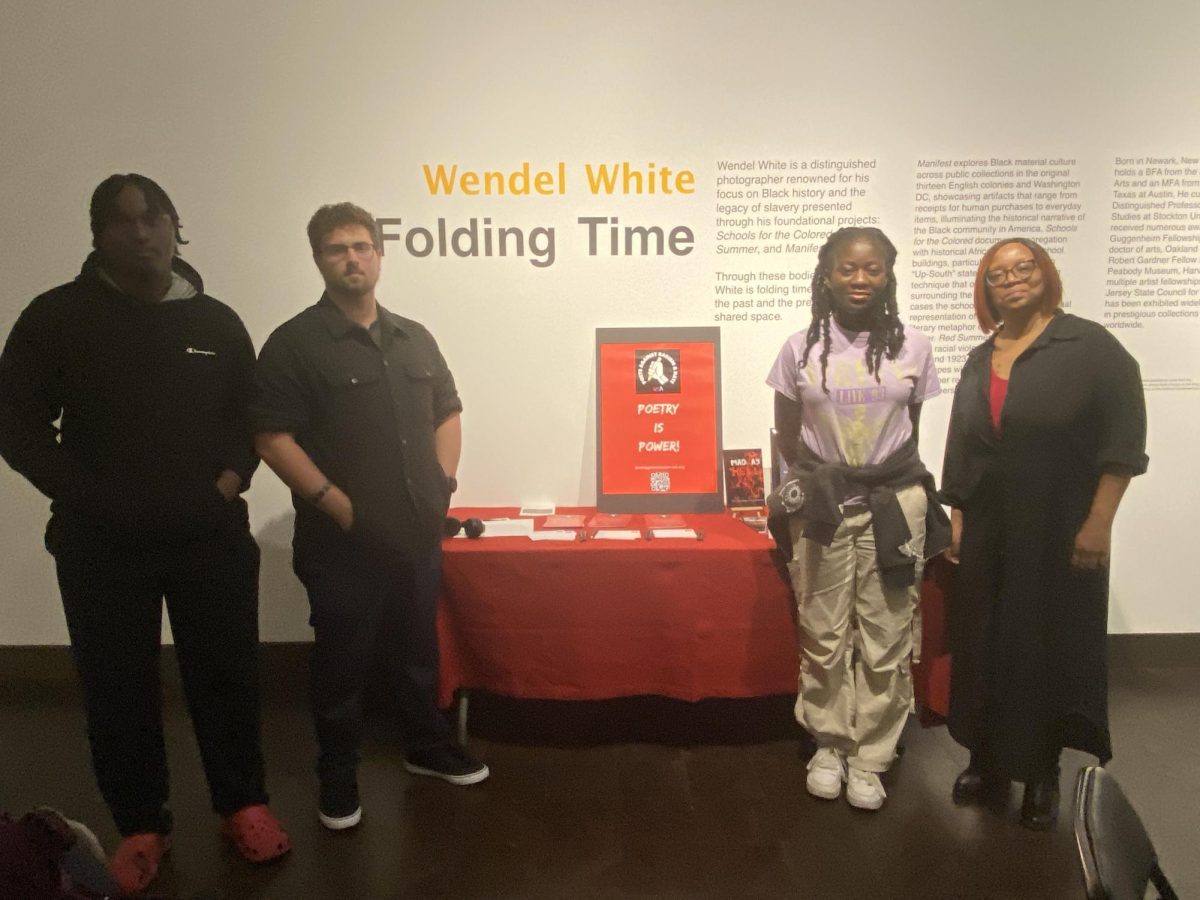

On Sept. 12, 2024, approximately sixty students, faculty, and Glassboro community members congregated at 301 High Street to witness the “Wendel White: Folding Time” exhibition.

Art enthusiasts sauntered through the exhibit Thursday at 5 p.m., perusing Wendel White’s body of work, “Schools for the Colored,” “Red Summer,” and “Manifest,” pausing to examine as they came face-to-face with a dark, and often forgotten history.

Much of White’s work represents a metaphoric “veil,” this idea conceptualized by W.E.B. Dubois, refers to the barrier separating black struggles in racial injustice and mainstream understanding.

With the conclusion of a brief introduction led by Mary Salvante, Director and Chief Curator, Award-Winning Photographer, Wendel White, who is also a distinguished professor of art and American studies at Stockton University, commanded the crowd’s attention.

White began by explaining the conception of his three portfolios on display. Citing his work from “Small Town, Black Lives,” which documents black settlements across America, as the derivative work for the pieces represented in the gallery.

“School for the Colored”, being the first child of this mother project, filled the left wall of the gallery.

Black-and-white images hyper-focused on segregated school buildings with blurred-out backgrounds. Some, not far from Rowan. Including but not limited to: Cape May, Woodbury, and Atlantic City being homes to these once segregated schools.

The areas in which White sought to immortalize in “Schools for the Colored,” were towns a part of the jurisdiction of “Up-South,” a concept described by White as northern states bordering the Mason-Dixon line that upheld southern traditions of segregation.

“You could look at these pictures without knowing the history, and it would look like any other,” said attendee Michelle Thieu, a chemistry major. “But with the context, you learn there’s so much more and there’s a mystery almost buried by time that you can’t see, and these collections bring them back to focus.”

Some schools were still functional, some abandoned and dilapidated, and some completely missing. White substituted absent or demolished buildings with black silhouettes to showcase what once was.

However, amongst the black silhouettes and gray-scale buildings, was one visual outlier; “The School for White Children, Brooklyn, Illinois,” which contrasted the rest by being the only whited-out silhouette.

Despite this town being a primarily black community, a small white population resided within its municipality–in turn, “this black town had built a one-room school, and hired a white teacher for a handful of white students that happened to live within the district,” said White.

Images of black-American historical artifacts, a project titled “Manifest,” sat adjacent to the schoolhouse pictures.

Some pictures in this section included; black and white baby dolls, used to study the effect of segregation on children; a skull, and wrought iron leg shackles, that once prevented slaves from escaping, still acting as a symbol of denied freedom.

Attendee and Glassboro resident, Lynda Gallashaw, said the shackles were the most compelling item for her.

“It’s sad to see that those chains are still in place and represented by strategies today,” said Gallashaw. “I still feel that same enslavement when looking at the fact that black people are still at the bottom of the totem pole.”

Gallashaw went on to correlate current events to White’s final section “Red Summer,” which presents civil-rights-related news clippings from the late 1910s and early 20s and is pictured beside the modern-day locations in which they took place.

Gallashaw not only discussed concern for violence against African Americans at the hands of police officers but went on to say, “I think brutality overall is up for black people…And when I look at brutality, it’s almost a fair share of police brutality as there is black-on-black crime, and that disappoints me.”

One of the headlines that photographer Wendel White focused on while discussing “Manifest” was from “The Dallas Express,” the top story being: “Wants Marriage Annuled; Claims Wife Has Negro Blood in her Veins” and below it, an article detailing a 1919 race riot in Longview, Texas.

Their message was clear: trivial white struggles meant more to them than violence against black people.

“One thing looking back does, is it opens up understanding that these kinds of things aren’t happening in isolation, it’s a history of behavior that builds up to a particular moment,” said White. “The more we understand that what we experience today has been baked into the system for a very long time, then we better understand what makes it invisible sometimes.”

Mary Salvante said she asked White to come to Rowan, for his work to serve as a reminder to students of the long and nebulous history of America’s racial injustice, in hopes his messages never get lost in time.

“I thought his work was so moving, and the stories are so important. Many of these stories aren’t well known, and they’re stories within our region,” said Salvante. “This compelled me to bring him to Rowan and share these stories with our students.”

“Wendel White: Folding Time” will be available for viewing until Oct. 26, 2024.

For comments/questions about this story DM us on Instagram @thewhitatrowan or email [email protected]

!["Working with [Dr. Lynch] is always a learning experience for me. She is a treasure,” said Thomas. - Staff Writer / Kacie Scibilia](https://thewhitonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/choir-1-1200x694.jpg)

!["Between poems, owner of Words Matter Bookstore and host Keryl Hausmann spoke, saying 'To listen to [poetry] is different than to read it.'" - Graphics Editor / Brendan Cohen](https://thewhitonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/IMG_0653.png)