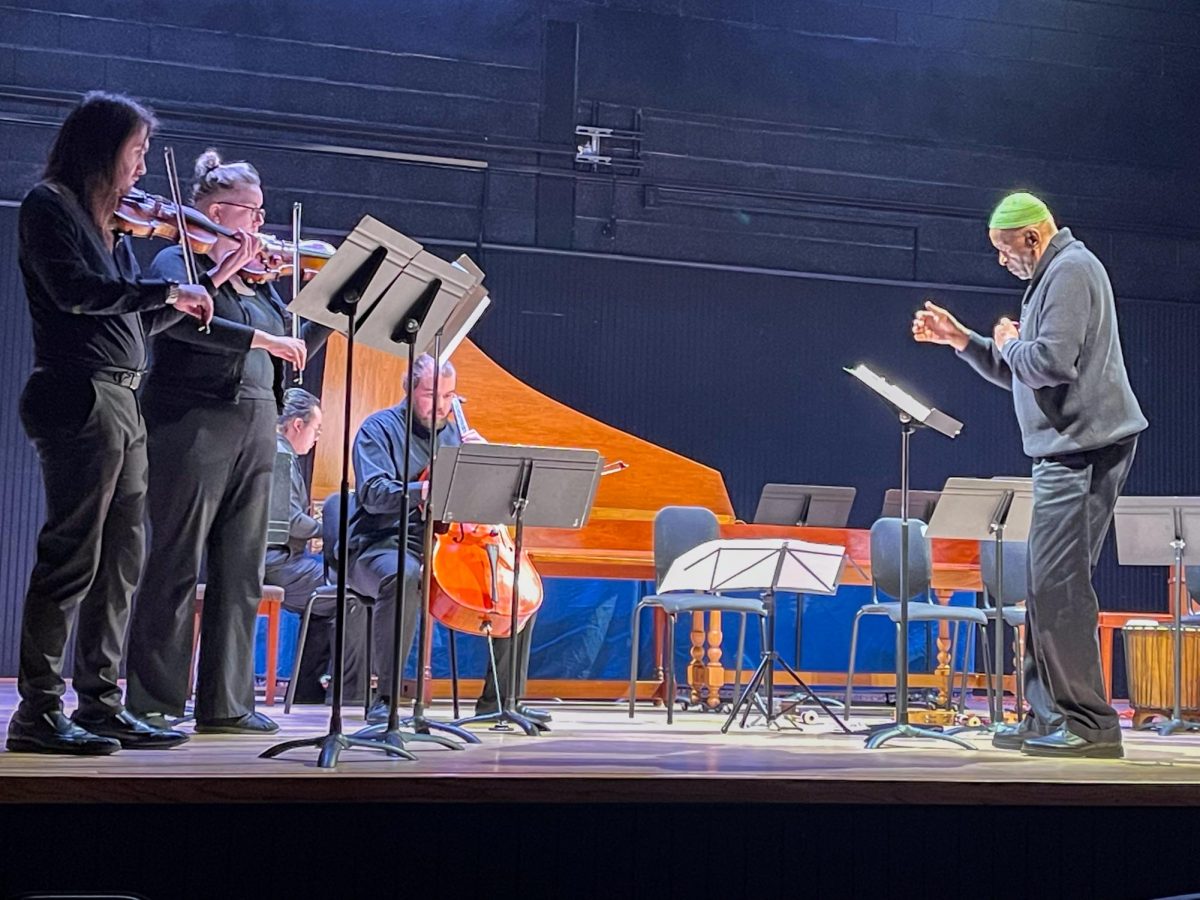

No matter what we do, no matter how we try, life changes—and that was the theme of the dismantling of the sand mandala, by the 72-year-old artist, Losang Samten in Discovery Hall, sponsored by the geology department and brought to the university by Dr. Harold Connolly. On Friday, April 11 in Discovery Hall, the former Buddhist monk deconstructed a sand mandala that he had painstakingly created over days.

The word is anicca, or impermanence. It is the foundation of Buddhist philosophy, and as it implies, nothing in life is forever. Dukkha, or suffering, is a key tenet in this Eastern philosophy. Buddhists believe that all our suffering in life is brought on by trying to hold onto things despite their impermanence. The more we let go, the more we will be at peace.

Traditionally, it was only reserved for monks’ eyes, the first time Samten shared a sand mandala in public was in 1988, at the American Museum of Natural History.

“It was really wonderful and shocking, both,” said Samten. “Wonderful because it’s a museum…55 or 60,000 people came, asked questions, and it’s just like a…shock because I had never done the mandala in the museum, so it was enjoyable but, at the same time, also more sorrow.”

Sand mandalas are not original designs. They come from an ancient tradition that some say originated with Buddha, in the fifth or sixth century. The designs are sacred, and the monks cannot replicate them from a picture: they must be memorized.

“These are not my designs; this is a design that [has] been done [by] so many artists in the past. I [cannot say] ‘Oh, this is my design’; it’s nothing to [do] with me, I put me to the side, me in the closet. I lock the closet and lock many things,” said Samten.

Despite having many designs memorized from his youth, there are simply too many to remember.

“When I memorized this, I was very young, though. Now, you mentioned your name to me, right? I forgot already…Back then, when I was in school, I had to memorize 500 pages [of sacred text]…[and] prepare for an exam. I said ‘Wow,’ and I did [that]…This design I did last year in Reno, Nevada,” said Samten.

Yet, surprisingly, the hardest part is not memorization of the intricate and complicated designs. According to Samten, it is discipline.

Art tends to evoke strong emotions from the artist during the creation process. However, in this case, that would be attachment, which Buddhists work to distance themselves from.

“[I feel] nothing…I don’t know how to explain [it], but nothing,” said Samten.

True to Buddhist form, he never feels the slightest bit sad about the sand mandalas’ destruction.

“No, not at all,” said Samten. “I feel sad for other things. I feel sad [that] I’ve lost my country, I [am] sad I lost my parents very young. I [am] sad for the many years of refugees. I [am] sad for what’s going on today in the world. Why we [are] still killing each other, I don’t understand. It makes me sad. But dismantle? Piece of cake.”

Every mandala focuses on more than impressive attention to detail. They each have a different meaning, from peace to knowledge. This particular mandala represents healing.

“I think I need healing, and I believe people may need healing,” said Samten.

Despite his decades of experience as a Buddhist monk, helping people with meditation and sharing important messages through his works, Samten does not consider himself a healer. He thinks of himself simply as an artist. Despite this, he never creates his own art.

“Why [do] I need to create? The beauty is there,” said Samten.

Samten was born in Tibet during a time of intense conflict. When he was born in 1953, the Chinese had increased their forces in Tibet, claiming to be there to bring Tibet into the future. Instead, they placed severe travel restrictions and brought war and sorrow. By the time he was five, the Khampa guerrillas, leading the Tibetan nationalist resistance, had begun their anti-Chinese campaign. By 1959, the Chinese had started executing Buddhist monks by the thousands. That’s when he and his family fled to Nepal.

“Oh, I remember [Tibet]. [I remember] losing everything. Losing everything. Danger for your life. Danger [to] my mom’s life. Danger [to] my dad’s life…even though at the age of six, I didn’t really know what the whole picture was, I can tell on the mom’s [and] dad’s face, something is dangerous,” said Samten.

He went to India in 1959 and soon thereafter entered the Buddhist monastery. He was selected to begin the rigorous training course in sand mandala painting, as it is called, and by 1988, after serving the fourteenth Dalai Lama, he moved to America to share the art.

Since 1988, this event has graced the halls of scores of universities and museums. It would not have been possible at Rowan University without Connolly’s tenacity.

“I have known Dr. Connolly since he joined Rowan University…I know that he’s a student of Buddhism,” said Vice President for Academic Affairs, Roberta Harvey. “My interest is in, partly, the way Dr. Connolly brings the idea of the earth and the environment into this adjacency with his meditative practices…he is absolutely a wonderful person.”

22-year-old Paige Sanders, a senior majoring in environmental science, explained her interest in the event through a unique lens.

“I just walked into class one day and started talking to Losang. [We talked about] just life, where we were from, my jewelry…[and] we traded: I gave him some of my feathers and he gave me this bracelet…[this] was fun, I liked [the dismantling],” said Sanders.

For comments/questions about this story DM us on Instagram @thewhitatrowan or email [email protected]

!["Working with [Dr. Lynch] is always a learning experience for me. She is a treasure,” said Thomas. - Staff Writer / Kacie Scibilia](https://thewhitonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/choir-1-1200x694.jpg)