On the morning of Monday, Oct. 12, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg released a statement on his platform announcing new policies which would “prohibit any content that denies or distorts the Holocaust.” While this is a change that is, by all accounts, very long overdue (by almost a decade since the Anti-Defamation League first began advocating for it), it is still, of course, very much welcome. This is a win in the fight against online hate speech and the systemic spread of misinformation, but there’s still a long way to go. Misinformation campaigns, online conspiracy theories and hate speech still present a real and credible threat to social and political stability around the world.

What are the dangers presented by these issues within the context of social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, and why should we be concerned about them? Academic studies intended to answer these very questions have told us a lot. They’ve told us that “hateful content diffuses farther, wider and faster and have a greater outreach than those of non-hateful users.”

They’ve told us that “ideological clustering observed in politically homogeneous echo chambers and algorithmic filter bubbles thus stands in contrast to the diversity of opinions found in face-to-face interactions. It ultimately jeopardizes political compromise as ill-informed individuals inhabit different networks in a society increasingly segregated along polarized partisan lines.”

And they’ve told us that “social media can act as a propagation mechanism between online hate speech and real-life violent crime.”

These dangerous trends are ongoing, and placing a ban on misinformation regarding the Holocaust, while important, will not reverse them. The spread of hate, conspiracy and misinformation through social media has become so deeply rooted in our societies, and so normalized, that New York Times columnist William Davies now calls this the age of post-truth politics. “How can we speak of ‘facts’ when they no longer provide us with a reality that we all agree on?” Davies asked.

Since 2016, sensationalized misinformation has become a staple in American politics. PolitiFact has found that, of all of President Trump’s recorded statements in their database, only 13% were either true or mostly true, and 71% were either mostly or completely false. President Trump recently posted a tweet that “Dems want to shut your churches down, permanently,” which was flagged as totally “pants on fire” false by PolitiFact.

Exaggerating and fabricating reality to trigger outrage and fear among followers is an exceptionally harmful campaign strategy, especially in this age of post-truth politics. In his show “Who is America,” comedian and social activist Sacha Baron Cohen wanted to see just how far people who regularly subscribed to President Trump’s conspiracy tweets would be willing to go based on their ill-informed beliefs. He talked to a man who had a good education and a good job, but who, on social media, repeated many of the conspiracy theories and misinformation spread by President Trump.

Cohen managed to convince the man that Antifa were plotting to “put hormones into babies’ diapers at a Women’s March to make them transgender.” He instructed the man to place small devices on three innocent people he claimed were Antifa agents, convincing him that the devices would trigger an explosion which would kill those people once he pressed a button that Cohen gave him. The question was: would the man press that button believing he would be killing those people? And the answer was yes, he would.

In a speech on the Fourth of July, religious activist Louis Farrakhan labelled Jews as “Satan” and the “enemy of God.” That speech was able to reach 1.2 million views before finally being taken down. Despite his well-noted history of rampant anti-semitism, racism, misogyny and homophobia that dates as far back as the 1980s, Farrakhan has enjoyed praise from many pop culture icons like Ice Cube, Nick Cannon, Stephen Jackson, DeSean Jackson, Jessica Chastain, Linda Sarsour and Chelsea Handler, many of whom have also repeated his hateful rhetoric through social media.

Nobody should want to see this kind of rhetoric become normalized, whether it be the vitriolic hate speech of people like Farrakhan, or the harmful conspiracy theories of people like President Trump.

Social media companies have long shirked the responsibility of having to maintain any semblance of truth or ban hateful content on their platforms, allegedly to avoid violating people’s freedom of speech. The obvious problem with that defense is that these companies are private businesses, not the U.S. Congress. As Sacha Baron Cohen so aptly pointed out in his speech, just as a restaurant has the right, and the moral obligation, to kick out a customer for shouting discriminatory and hateful slurs at other people, internet companies have the same right and moral obligation to kick out users for hate speech and flag false information.

Nobody asked for six CEOs in Silicon Valley, who were not democratically elected or federally appointed with any due process, to have more control over the global dissemination of information than just about any other institution. The very idea that such conditions could exist seems inherently undemocratic and completely undesirable, but this is what we’ve got. Now, in order to live up to the role they’ve crafted for themselves as the de facto arbiters of truth to the world, they need to acknowledge and fulfill certain responsibilities.

They have a responsibility to relentlessly fact-check all media outlets and all public and political figures on their platforms. They have a responsibility to cease from using algorithms to micro-target their users with content that feeds into pre-existing biases and that intentionally triggers outrage and fear. They have a responsibility to use their platforms to facilitate healthy dialogue and promote diverse thinking. They have a responsibility to be fully transparent about what specific steps they plan to take to regulate their platforms. Finally, and most importantly, they have a responsibility to ban hate in all its forms. It shouldn’t matter if it comes from a ‘troll account,’ a cultural icon, your next-door neighbor, or even the president of the United States.

For comments/questions about this story, email [email protected] or tweet @TheWhitOnline.

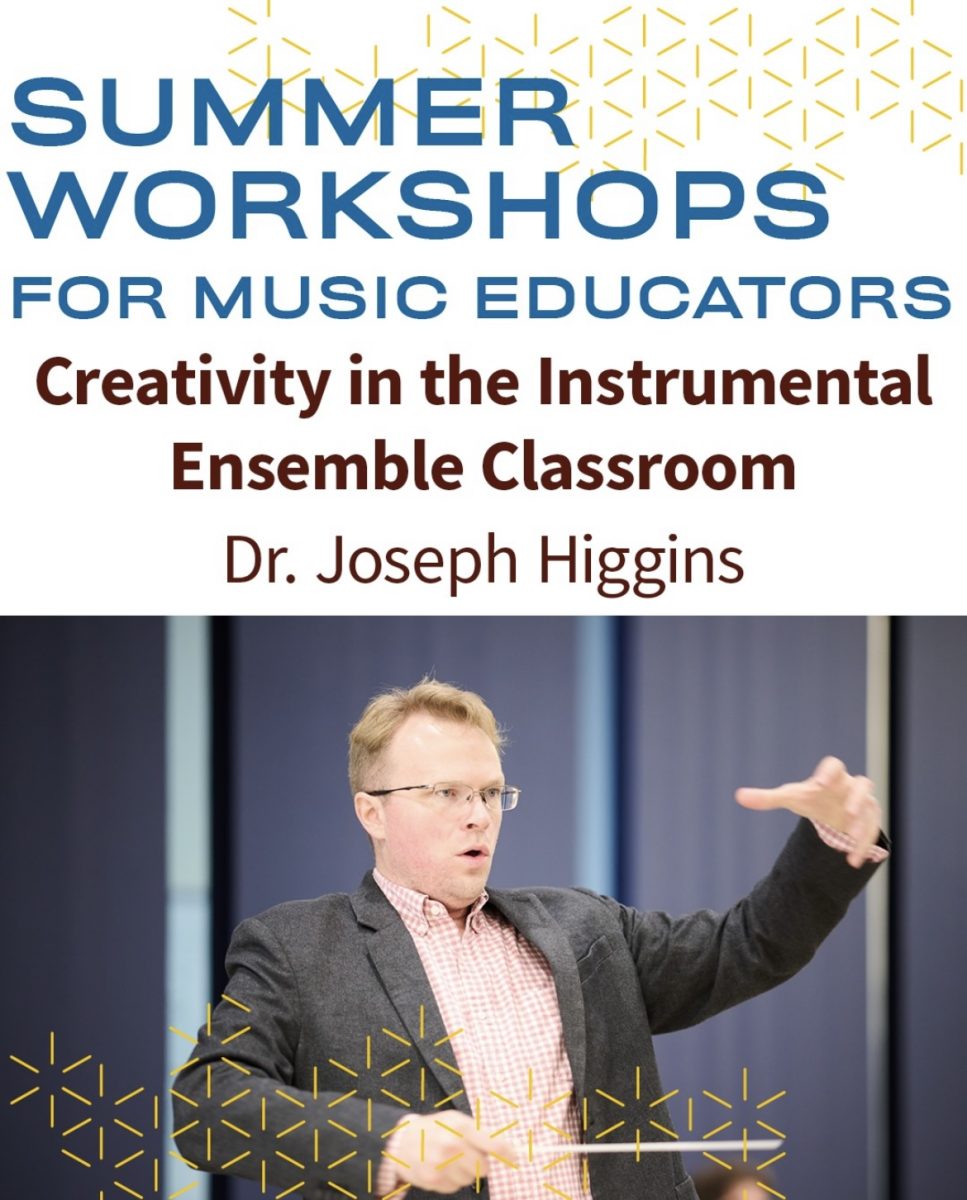

!["Working with [Dr. Lynch] is always a learning experience for me. She is a treasure,” said Thomas. - Staff Writer / Kacie Scibilia](https://thewhitonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/choir-1-1200x694.jpg)