Editor’s Note: This opinion article contains descriptions of violent acts committed during the Holocaust, which may be distressing for some readers.

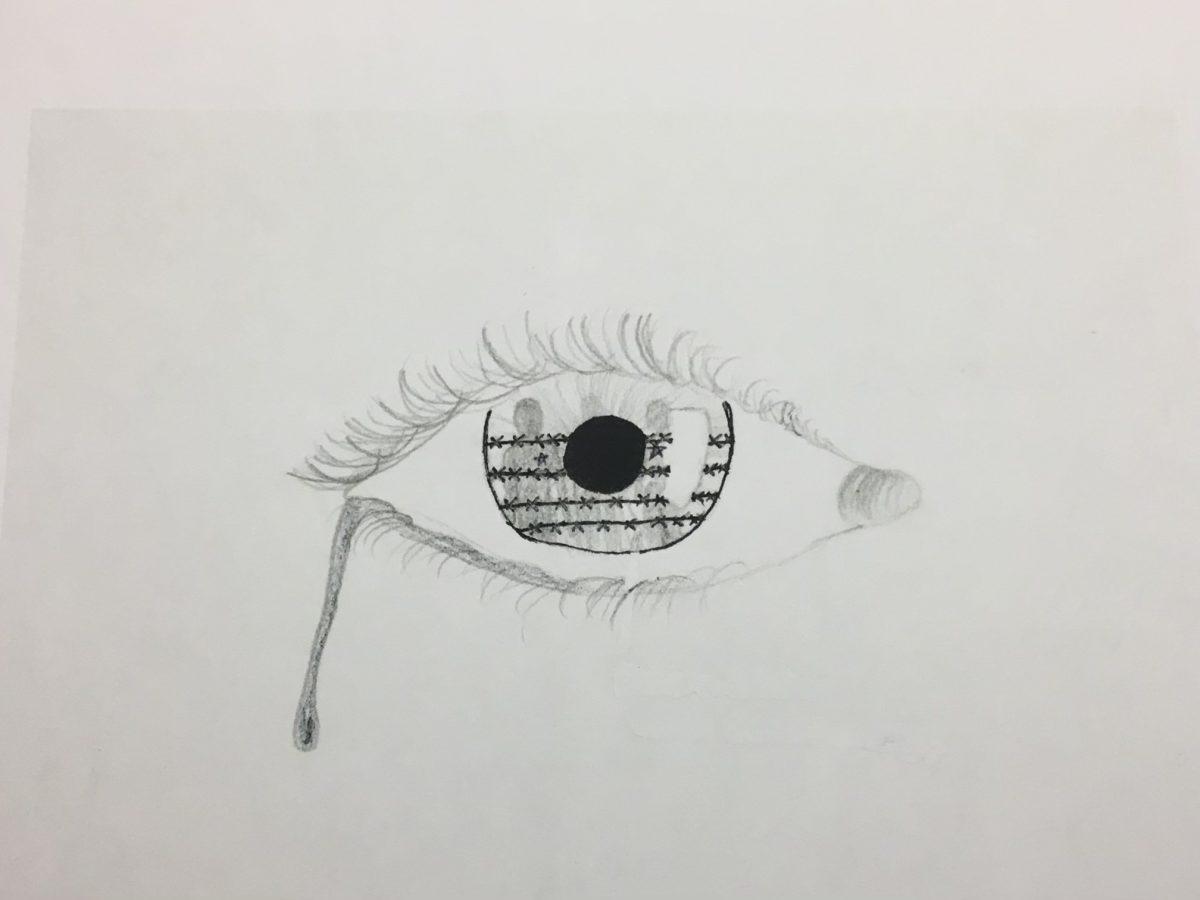

What does it mean to remember something that never happened to you, or even during your lifetime? How can we grasp the weight of this loss when we can hardly comprehend what might have been — what should have been — if this had never happened? Renowned author and second-generation Holocaust survivor Gila Lustig once said that “whether we have experienced it ourselves or else through our parents, the past overshadows everything and faced with the horror even the slightest feeling of privacy and inwardness falls completely silent.”

So it was, on a late autumn evening in 1938, between Nov. 9 and 10, that the continent of Europe went to sleep, not knowing the atrocities it would wake up to see in Germany, Austria, and the Sudetenland (an area of what was then Czechoslovakia inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans). On that night, the systemic oppression of Jews had taken a sudden and horrible turn toward organized violence. That night came to be known as Kristallnacht.

Over the next 48 hours, 91 Jews were murdered, and many more died in the days that followed. Some died from injuries sustained during that period, and hundreds of others were driven to suicide by what they had experienced. 30,000 Jews were extrajudicially apprehended and sent to concentration camps, hundreds of synagogues were destroyed by rioters, and approximately 7,500 Jewish businesses were ransacked and looted. All of this is on the basis of religion.

In the aftermath, Hitler’s Reich declared that Jews were to blame for his party’s brutal and sadistic pogroms, and a fine of 1 billion Reichsmarks — equivalent to $400 million in America in 1938 — was forced upon Germany’s already reeling Jewish community.

These past 82 years have not been enough to erase the hurt felt by Jewish communities and families around the world, and perhaps no amount of time will be. As a kid, I remember just being told that my grandmother grew up in a time when there were some very bad people who didn’t treat her fairly because she and her family were Jewish like I am. I was too young then to grasp just how horrible it really was.

But eventually, when I was old enough, my grandmother and great-aunt passed on to me their full story. I learned how they were driven from their homes in what was then Poland, first by the Soviets, and then the Nazis. I, of course, never met my great-great-grandparents. However, having learned how tragically their lives were cut short as a result of the Holocaust is a constant source of motivation for me to keep their memories alive. Their names were Laura and Leon Tennenbaum.

Coming from a family of Reformist Jews, I was raised with the belief that the value of one’s life is not determined by whether you are accepted into heaven or sent to hell. The true meaning is found in the memories you leave behind. The good. The bad. All of it. We will never truly be gone from this world as long as there are people left to remember who we were. Those memories are everything. The stories and memories we leave behind for future generations are what will keep us alive.

These six million souls, from whom everything was taken, cry out to be remembered — by us, the next generations. And we say: may their memory be a blessing. But we also say: may their memory be for a revolution.

Honoring all these singular human beings — sisters, brothers, sons, daughters, mothers, fathers, cousins, spouses, and friends — means fighting relentlessly for this most sacred mantra: Never Again. Their memory must be a call to action to speak out against hate, oppression, injustice, intolerance, discrimination, and xenophobia whenever and wherever we see it.

USC Shoah Foundation Director Stephen Smith once said “There is a difference between looking back at the past and saying never again and being actors in the present. It takes you to know deep inside your mind, and inside your soul, that when you see this happening to others, you will be an actor in their defense.”

He also went on to say that “the microdecisions that people make to love when all around them is hatred — to reach out to your neighbor in times of trouble — those individual choices make up a galaxy of stars… and as we look at them all and we step back, we see the possibility of what it means to live.” These constellations of light and positivity grow every time someone chooses love over hate. And when the world around us gets dark, they are our guiding lights.

There is an idea in Judaism called Tikkun Olam, which means to make the world a better place. It represents the sacred obligation of every human being on Earth. Everything from the smallest act of kindness to the biggest leap toward positive change is Tikkun Olam. For every soul whose life was cut short by heinous acts of violence, we have an obligation to keep telling their stories and keep honoring them by engaging in Tikkun Olam. That is how we make their memory a blessing.

For comments/questions about this story, email [email protected] or tweet @TheWhitOnline.

!["Working with [Dr. Lynch] is always a learning experience for me. She is a treasure,” said Thomas. - Staff Writer / Kacie Scibilia](https://thewhitonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/choir-1-1200x694.jpg)