A four-year-old Melissa Martinique got ready to go to the hospital to have surgery on her heart. Her parents kept her calm by explaining the operation in a way that was understandable to a child and familiar to Martinique.

“My mom sewed,” Martinique said. “She sewed my blankets and my toys, so she said, ‘You were born with a hole in your heart. We’re going to take you to the hospital and they’re going to sew your heart how mommy sews your stuffed animals.’”

Martinique, a junior early childhood education and literacy studies major, has an atrial septal defect, also known as ASD. ASD is a congenital heart defect that affects the wall located down the center of the heart.

The heart is split into four chambers: two on the top, and two on the bottom. The wall that divides the left and right sides is called the septal. The septal of Martinique’s heart had several holes in it, which allowed for blood to flood into chambers it was not supposed to be in. Usually it’s one large hole, but Martinique had several small holes. Her surgery was to close the holes before the defect worsened and deoxygenated blood flowed through the body.

Compelled to help others understand and live with their disabilities, Martinique, 21, has dedicated herself to becoming a special needs teacher.

Melissa Martinique was born on September 2, 1996. She has dirty blonde hair, wears thick-rimmed glasses, and always wears a smile on her face.

Her parents, Bonnie and Steve, had no clue their only daughter had a heart defect.

In October of 2000, just after Martinique had turned four, she had a run-of-the-mill chest cold. Blaming her mother’s intuition, Martinique’s mom took her to her pediatrician. Her doctor since birth listened to her heart and lungs and heard something she hadn’t before. A small soft murmur.

While heart murmurs can be common in children and are usually outgrown, Martinique’s pediatrician suggested a visit to the cardiologist’s office.

Everyone expected her murmur to be nothing, but after a few tests, it was determined she had ASD. She had the heart defect since birth but it was only noticeable because of her congested lungs. The murmur was otherwise silent.

A month after that doctor’s appointment, Martinique was scheduled for minimally invasive septal-sparing open heart surgery. Martinique’s surgery was relatively new in the United States and was done by leading cardiovascular surgeon Stephen B. Colvin at the NYU Langone Medical Center.

Instead of cutting down the center of the chest and cracking open the rib cage, Colvin cut a five-inch incision, which is now just under Martinique’s right breast. There is another small scar a little further down, which allowed for fluid drainage.

After three days in the hospital, Martinique was free to go home. She was also free to live a normal life with no medication or restrictions.

“I’m so very lucky,” Martinique said about her condition. She is blessed to have had Colvin perform her surgery.

Martinique’s parents had always told her she had a hole in her heart, but when she was 12, she wanted to know more. She asked what the condition was called and began to research it. This research led her to look more into fetal defects. Martinique learned that during pregnancy the heart is the first thing to form and one in 100 children is born with a heart defect.

“No wonder there are mess-ups,” Martinique said. “Our bodies are so complex.”

Dance has been an important aspect of Martinique’s life since right before her surgery. She danced for 14 years. After her recovery, she got back to dancing, doing many different styles including tap, jazz, lyrical, contemporary, ballet, musical theater, hip-hop, and kickline.

When Martinique was 11, the children’s classes at her dance studio needed an older dancer to lead the toddlers during the recitals. She always liked little kids and being the teacher’s pet she was, she volunteered to help out.

Throughout those large classes, there were children with disabilities, such as autism and Down syndrome.

“It’s hard when you have like 15 other three or four-year-olds, and then you have this one child who has a disability and it’s not that they are inherently bad, but they need the extra help,” Martinique said. During the classes, she would help the children who had disabilities individually.

“These children can do what is expected of everyone else, just differently,” Martinique explained.

She spent seven years working with children with disabilities, watching them grow and grasp the dances.

“It’s really cool seeing a child struggle or lag behind and then all of a sudden something clicks and they get it,” she said.

When Martinique was 16, she worked with a girl named Allie who had Down syndrome. She was a very small, non-verbal child who was engaged but sometimes didn’t participate in the lessons. At one time, she didn’t want to touch her toes with the rest of the children. Martinique and the other instructors couldn’t figure out why.

One day, Allie was standing across the room as the other students began stretching in their circle. Allie, from the other side of the room, also began stretching. They figured out Allie just didn’t want to stretch with everyone else but she didn’t know how to articulate that.

Allie could do the stretches and dances like the other students, she just learned differently than they did.

“It was really cool to work so intimately and watch this child grow and be successful and be a part of that,” Martinique said.

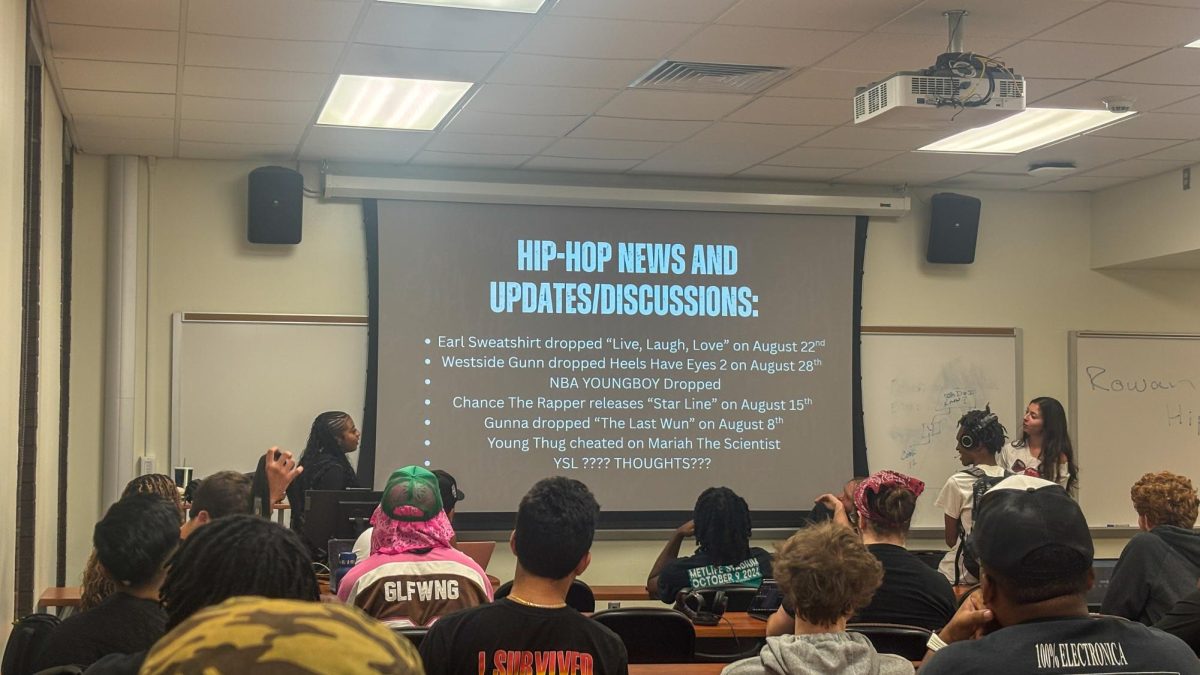

Martinique described a mini-life crisis during high school. She was a part of the school band all four years, taking on roles including section leader of the flute section and drum major. She loved band and music and thought of being a music director. But during her senior year, she realized a music director was not the path she wanted to take.

“What else can I do?” Martinique questioned. “Who else am I?”

Martinique thought back to volunteering at her dance studio and how the special needs students absolutely charmed her.

After graduating from West Milford Township High School, she came to Rowan University.

“I’ll go wherever the wind blows,” Martinique said when describing the age she would like to teach.

Martinique has already completed the Praxis tests she needs to become a teacher. She had to take three separate tests, each focusing on different sections of learning: early childhood, teaching reading, and special education. To take the burden off her shoulders, Martinique took all within a month.

Martinique is a part of three clubs at Rowan University. She is an Admissions Ambassador, where she tells interested students on tour a story of her piggy bank named Sally, who helps hold her quarters for laundry day. She also is a member of the Ballroom Club.

Martinique is also the vice president of the Student Council for Exceptional Children. The club members volunteer with people who have disabilities, advocate for them, and educate the community.

Each club allows Martinique to be the outgoing and extroverted woman she is. She met her two best friends through Admissions Ambassador. She found a love for working with older individuals with disabilities through her position with the Student Council for Exceptional Children.

“She is very motivated within the field and that’s always something I admire when someone is really dedicated and truly loves what they’re doing,” said Tyler Jiang, who works with her in admissions.

“Melissa has so much energy all the time,” said Lauren Burch, also an Admissions Ambassador. “It’s never a dull moment with her and you can always expect to have a great time when Melissa is around.”

Martinique only has one small hole left in her heart today and one question that hasn’t been answered.

“I want to find an answer one day, to see if it is genetic,” she said.

Doctors won’t be able to ever give her a response to that question because there are too many unknowns.

To Martinique, it is very clearly a genetic heart problem, but still, she has always been “very proud” of her heart issue.

Martinique is suspicious because of her family history. Her mother’s father passed away from a heart-related issue when he was 37. Her mother’s sister has a mitral valve deals, which is a problem in the blood flap in the heart.

“It really did stem from my own research into my own past and identity of who I was,” Martinique said about her passion for special needs. “It was a catalyst for me to go out and be interested in these individuals.”

“That’s what got me into special ed initially,” Martinique explained. “My disability.”

For questions/comments about this story, email [email protected] or tweet @TheWhitOnline.