Right now, you are hopefully holding a physical newspaper.

One of my favorite parts of writing for the Whit is that we print physical newspapers each week. As a writer, it’s an incredible feeling to see your words immortalized on an official piece of paper, and even more incredible still to see people reading them.

I love walking past the tables and counters where the staff at the Whit have dropped off newspapers, to see that a paper is open and has been read by students and staff. It makes me feel like all this work that the Whit does isn’t for nothing.

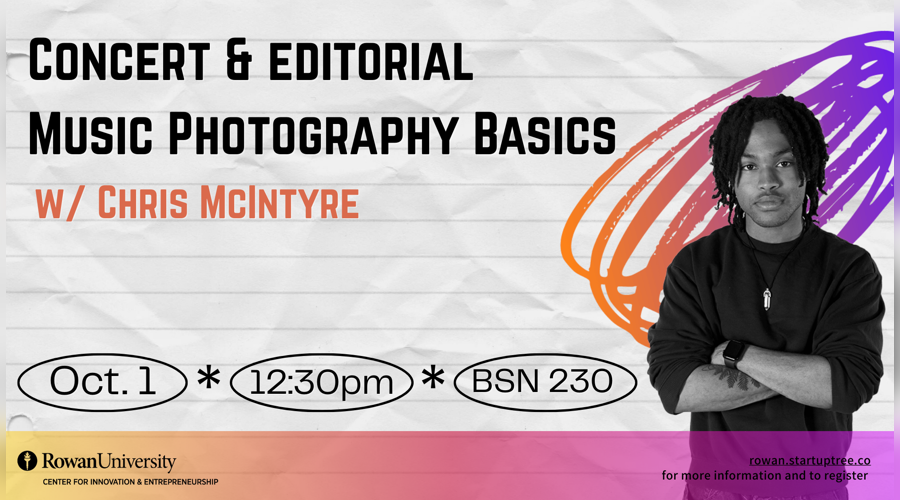

But of course, the work of the Whit isn’t for nothing. Every week, our writers are working hard to ensure that no stone goes unturned. If something has happened or is happening at Rowan, odds are one of us is on the scene.

By investigating things, talking to people, and reporting on events, we hold institutions accountable, leaving behind a historically accurate record of all the things that happen on our campus and within our community–good or bad.

Therefore, journalism is a function of accountability. Every time the university sets a deadline for the Student Center expansion to open, a writer from the Whit is knocking down the door, asking relevant parties questions and getting their word on things.

The next time the deadline is pushed back, there’s a physical record that the university has failed to keep its word.

This has been the case with journalism since its inception, and it’s why freedom of the press is so important. Consider, however, how the internet changes this function of journalism.

Every time an article is published, and it’s discovered that there’s an error: say for example I spoke with a Lily Miller but her name was spelled Lilli Mallard in the article, then on the digital version of the article, the Whit would issue a correction. Readers would be able to see at the top of the article before they begin reading, a line of text briefly correcting the blunder.

What happens when news channels, or other media in general, stop owning up to their mistakes?

That’s a big question that I do not have the answer to, but what I do know is that the internet, and digital media as a whole, make it much easier to gloss over mistakes and correct them as they come.

If I read an article published in 2012 but it has been corrected numerous times over the year with no record of the corrections, I would have no idea if what I’ve read is true or not.

Our physical newspapers may be a “relic” of the past, of a time when the only way to get the news was by reading it, and the only way to read the thoughts and opinions of your peers was by seeing them in print, but they are also a testament to careful journalism.

Our writers, and then editors, spend a lot of time each week pouring over articles to ensure that there is integrity in each word so that once the physical papers are out there, they are as accurate as they could have been.

And if somebody makes a mistake, it is memorialized in print.

Believe it or not, I think that is a good thing! We live in a time where we can erase our mistakes as they come and pretend they didn’t happen. But they did, and that’s okay.

Erasing our mistakes, and trying to change the past is a slippery slope. Ethically, I start asking the question of, where we draw the line. I feel perfectly content editing a DM I’ve sent if there’s an error, and just putting in a little asterisk (*) to show why I edited my message, but what if I wanted to change the meaning of what I said entirely?

Our social media platforms have safeguards against this, such as alerting the other party when you’ve edited something, or not allowing you to edit something after a set time has passed.

However, news sources are not held to the same standards. They can alter their digital content as they see fit, potentially making the way for them to rewrite the past.

I’m hopeful that that doesn’t happen, and to be transparent, I don’t think it will. It’s very Orwellian and honestly, it sounds really time-consuming. However, that doesn’t change the fact that I love our newspapers. They are tangible, their content is permanent and very much human.

On Feb. 1, the Star-Ledger, New Jersey’s largest newspaper, printed its last physical newspaper. The outlet will be continuing as an entirely digital operation and is taking with it the vestiges of human error.

There is an argument to be made that in doing this, the Star-Ledger is also choosing to lose a passive readership. When I see a copy of the Whit sitting open, that’s proof that somebody going about their day, made a choice to open a newspaper and read at least a bit of it.

Without the input (seeing a newspaper) what will inspire somebody to read a digital copy of the Star-Ledger, as opposed to getting their news from somewhere far more convenient, or perhaps not at all?

As for how the Star-Ledger will choose to use its newfound digital freedom, it likely won’t be to rewrite the past. But what about an artist? What about a regular everyday person, archiving posts on Instagram to make way for the new person they are today?

The authenticity of print media is what draws me to it, especially in an age where we can pick and choose what the world sees. When change requires effort, it means that we put more thought into what we create. It means we put more thought into each change we make.

So, here’s to print media, with all the honesty in its mistakes.

For comments/questions about this story DM us on Instagram @thewhitatrowan or email [email protected]