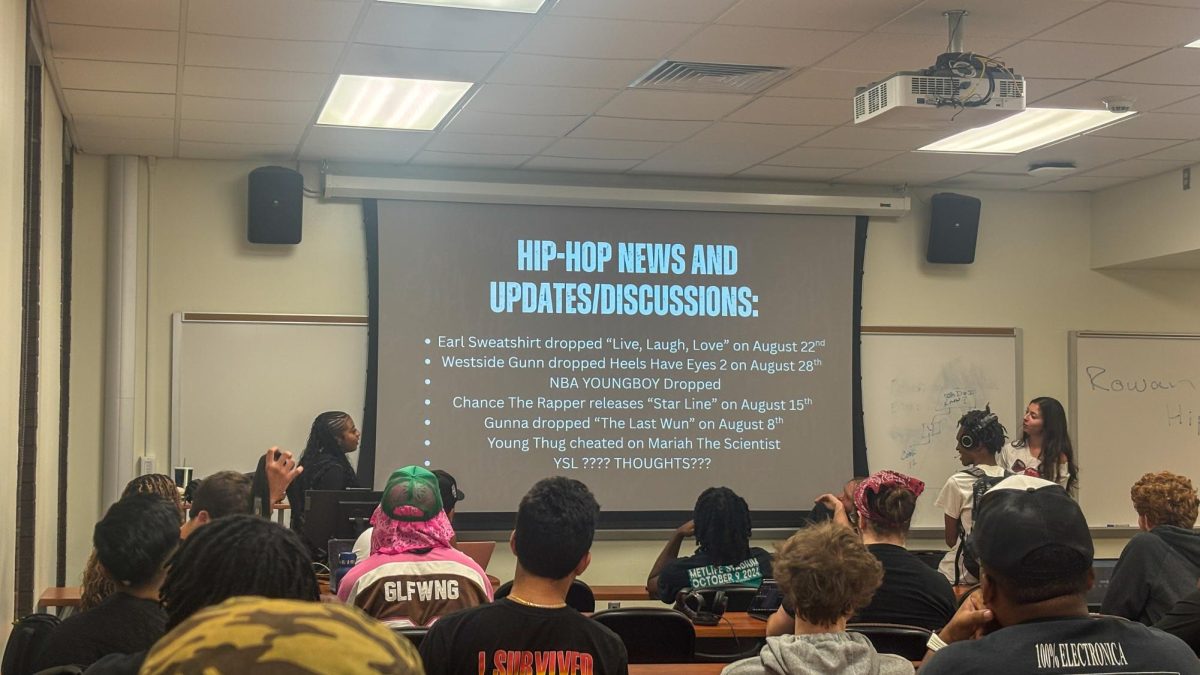

Following the documentary, “Paris Noir: African Americans in the City of Light,” showcased at Rowan University on Feb. 20, students reflected on the history of African-American influencers in Paris, questioning the presence of black history, or lack thereof, in New Jersey’s K-12 curriculum.

The one-hour film, by Joanne Burke, details the extraordinary stories of African-Americans such as Eugene Bullard, the first African-American military pilot who flew for the French Army; Josephine Baker, a dancer turned Free French member and civil rights activist; and Louis Mitchell’s Jazz Kings, the first commercial jazz band to play in Paris and pioneer the jazz movement in France.

“Paris in the 1920s for African-Americans was a city unlike any other in the world. It represents freedom, freedom from segregation but on a broader level, the ability to pursue one’s dreams in the broadest sense and to be accepted for what you are…,” said commentator, Brent Hayes Edwards, in the film.

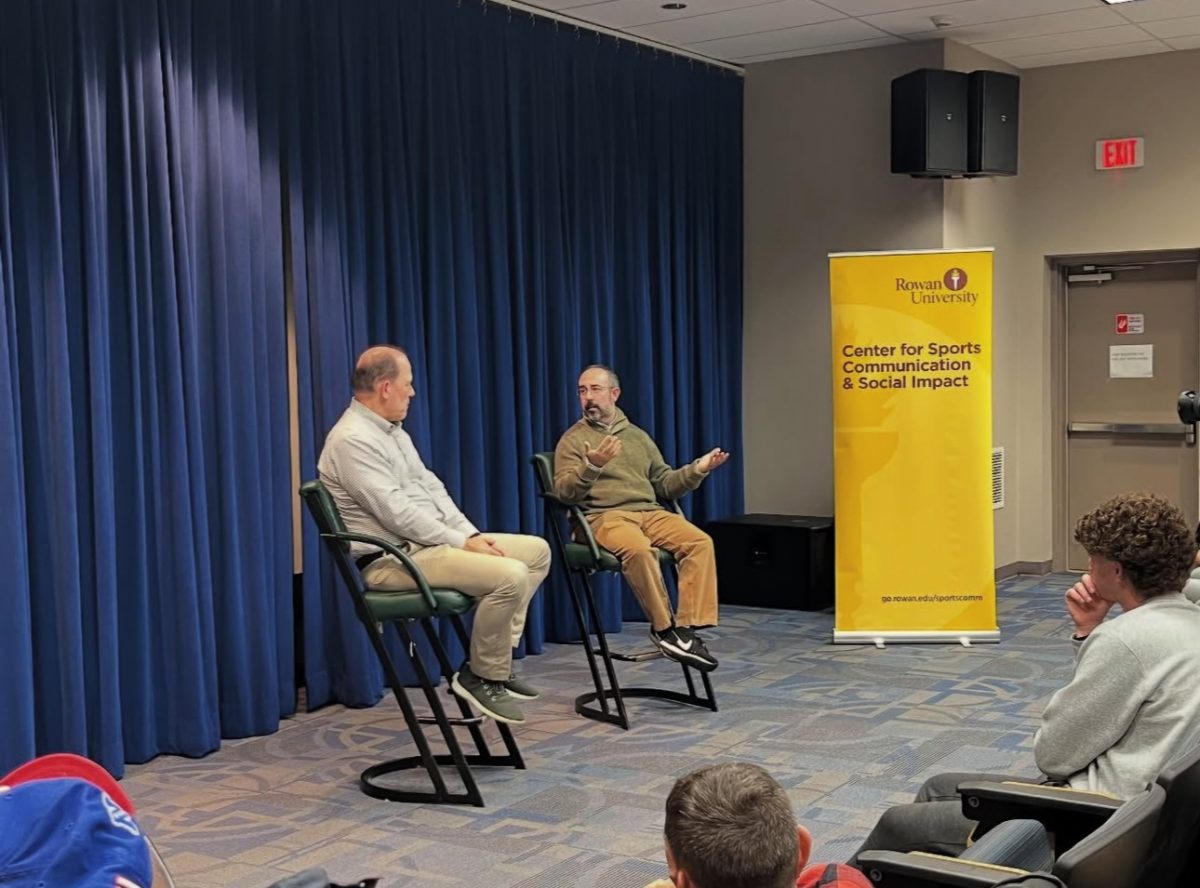

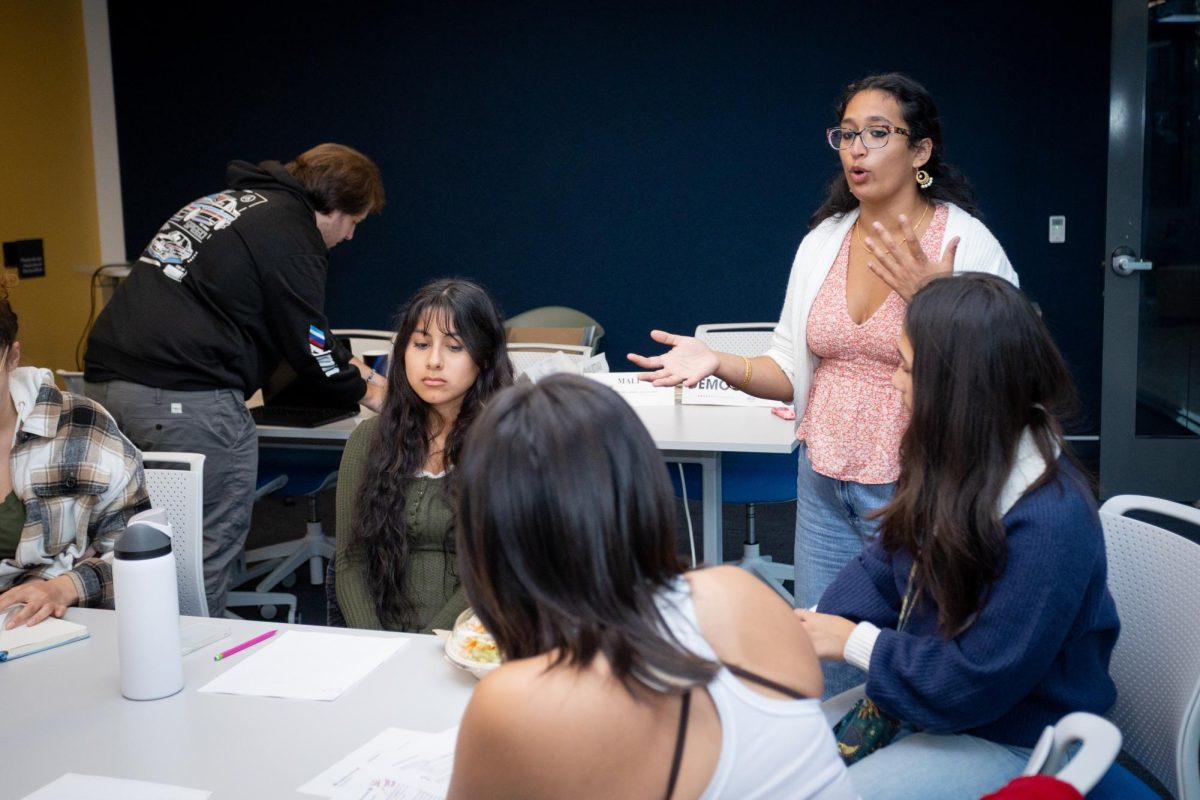

Associate producer Julia Browne presented the film Tuesday night in room 221 of the Chamberlain Student Center.

“There is still a respect for black Americans in France. People know of the black history,” Browne said.

Opening the room for questions after the film, Browne, a “black Paris travel expert” and founder of Walking the Spirits Tours, shared her experiences traveling abroad and living in Paris.

“As an African-American, it’s a rare opportunity to really [ask yourself] where am I in this world? What am I going to be in this world? Who am I going to be in this world?” Browne said.

While reflecting on the film, students began to question the current representation of African-Americans in the U.S. and the minimal coverage of black history in our school systems.

“There is a tendency to maybe be smothered by your situation of living here, but there is a big ol’ world out there and it’s not the same outside everywhere else,” Browne said.

Junior history major Jasmine Johnson attended the event for both educational and personal purposes.

“I wanted to go to Paris, but now I want to go even more,” Johnson said. “My dad’s a big jazz fan, we used to listen to jazz [together] when I was younger, so this was really interesting and intriguing for me.”

The 28-year-old, with a minor in Africana studies, noted that the K-12 system she went through in Winslow, New Jersey, “lacked” in teaching students African-American history.

“Black history was just for that month. After that it was back to ‘history’ and African-American history is American history, and it’s always taken out,” Johnson said.

Dr. John T. Mills, the assistant director of Multiculturalism and Inclusion Programming at the university furthered the conversation by showing students the New Jersey Amistad Commision.

“For the education majors here, in my opinion, this should be part of their curriculum. It’s not,” Mills said.

According to the commission site, following the passing of the bill in 2002, it was “presumed that the goal would be to introduce African-American history into the K-12 curriculum and to develop public programs on African-American history.”

When asked if any members of the audience had heard of the law, not a single hand was raised.

“Please, talk to your peers about this. Ask them, ‘Have you heard of this?’ The real question is, ‘Why haven’t you heard of this?’” Mills said.

The dialogue grew into a discussion regarding the insufficient coverage of black communities in the media beyond Black History Month, and the representation of minorities within the Rowan community, a primarily white institution.

“At our office, we encourage our melanated students, more richly melanated students to get involved. You must get onto those boards. You must be a part of SGA. [You] must become a part of The Whit. If you don’t have a voice at the table it’s going to be hard to create change,” Mills said.

Mills continued to urge the crowd to share their experience of the film with others and to “continue the conversation, pose questions and create allies among all races.”

“You all as students have a lot more power than you think you do,” Mills said. “You can get things done. The change may not appear while you’re still sitting here, but you may be able to come back and find that change.”

Relating her experience to that of many other African-Americans throughout history, Browne compared the “intertwining stories” of African-Americans to a “skein of wool.”

“I’m just one of many people telling the story and I feel, yeah privileged, but you know those are words that everybody says. They feel blessed, they feel privileged, they feel honored… I just feel that it’s my place to be doing this, and I’m so glad that I am doing this,” Browne said.

To the students of Rowan, “The ball is in your court,” Browne said. And to the students of color, “We got history all over the world, go find it. And I hope that this [film] opens a door for questions, but also for finding your place in the world.”

For questions/comments about this story, email [email protected] or tweet @TheWhitOnine.