German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche once said that truths are “illusions of which one has forgotten that they are illusions.”

What, exactly, does this mean? If we accept this premise, why do we believe what we believe if our supposed truths are illusory?

The notions of truth and worldview are slippery concepts. This editorial, of course, is no assertion of truth, but is rather an exercise in challenging the notion that we can access objective reality.

Our worldviews are just that: views, and whatever we currently subscribe to is only one lens of many through which to view the world. These lenses are formed by the information we are exposed to over the course of our lives.

The further we interrogate what we believe, the more we realize it’s been shaped by the sources that report it to us.

Politics and religion are likely the two topics our prevailing cultural narrative urges us to stay away from during polite conversation because of the strength and invisibility of the lenses from which these constructs emerge.

Take, for instance, your understanding of President Donald Trump as an entity. You’ve likely never met him or interacted with him. 100 percent of what you know about him comes from the rhetorical situations through which he is filtered to you. If you follow Breitbart, Fox News and The Wall Street Journal, you are likely operating in the conservative, more pro-Trump lens. Conversely, if you watch MSNBC, late night talk show monologues and “The View,” you might be entrenched in the liberal, anti-Trump lens.

Even if your media diet is more ideologically diverse, it’s still never coming to your from your own firsthand experience. Parameters have been set, language has been chosen and the entire situation has been created and delivered to you, the consumer.

This notion extends much beyond Trump or any ephemeral political dialogue of the day. For instance, your ability to read these words at this present moment is a further lens that you’re entrenched in, that being the English language. This is a created rhetorical structure that you live by that writes the narratives of your life.

If we are limited to tidily wrapped reports of world events that are further distanced from reality via translation into language, then it starts to become clear that whatever we believe may be far from the truth.

Aside from politics, religion is another pertinent example of this notion. Most religions see their spiritual path as the ultimate truth, with their respective holy books and savior as the only path to salvation. But the more we begin to think about religion globally, the more absurd it seems to claim one is paramount. Thousands of religions exist on earth, and most differ drastically from the next. How, then, can one be claimed as the utmost truth, if the vast majority of people believe something completely different and claim their path is the only way?

When pressed for the origins of their belief, only one answer likely lies at its foundation: It was passed down by a preexisting structure/lens that the believer stepped into.

This isn’t to bash any religion or political viewpoint. Rather, the point is to recognize that whatever you believe may only be a belief, and clinging onto it as if it’s part of your identity and an objective truth can lead to trouble.

Much strife in our world seems to originate from the failure to recognize an illusion as an illusion, as Nietzsche puts it.

The recent mosque shooting that left 50 worshipers dead. The shooting that left members of Congress wounded and Rep. Steve Scalise fighting for his life. The Crusades. Islamic extremism. Small-town murders. Gang rivalries.

These terrible events all have in common that the perpetrators viewed their way of life and belief system—their religion, political views, gang, temporary emotions—as objectively true and more valuable than differing lenses. When people combine their sense of self with the constructed lens that shapes their world, they can be willing to take a life or sow division in order to preserve their constructed way of being.

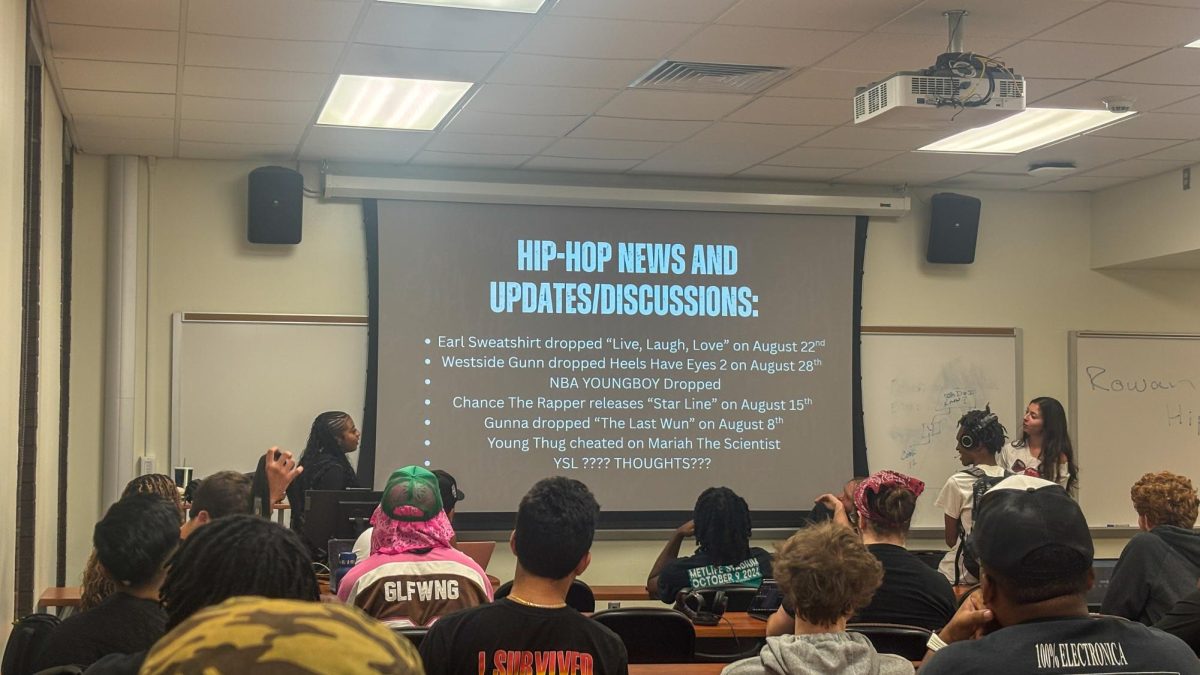

To bring this philosophical treatise closer to our experiences, perhaps we can think of this insight as the true value of a college education. Rather than creating “woke” social justice warriors or cogs in the capitalist machine, maybe the point is to provide students with more lenses through which to view the world. Education scratches at the surface of a possible objective world. But it seems we’re wired to never actually access this world. Recognizing this fact, stepping back and viewing the lenses available to us might create a more understanding and empathetic way of being.

Don’t lose yourself in your sense of what you think the world is. It’s probably far different from that. Take a breath, stare into the impenetrable nature of reality and be humbled.

That’s a lens our modern society would likely benefit from looking through.

For comments/questions about this story, email [email protected] or tweet @TheWhitOnline.