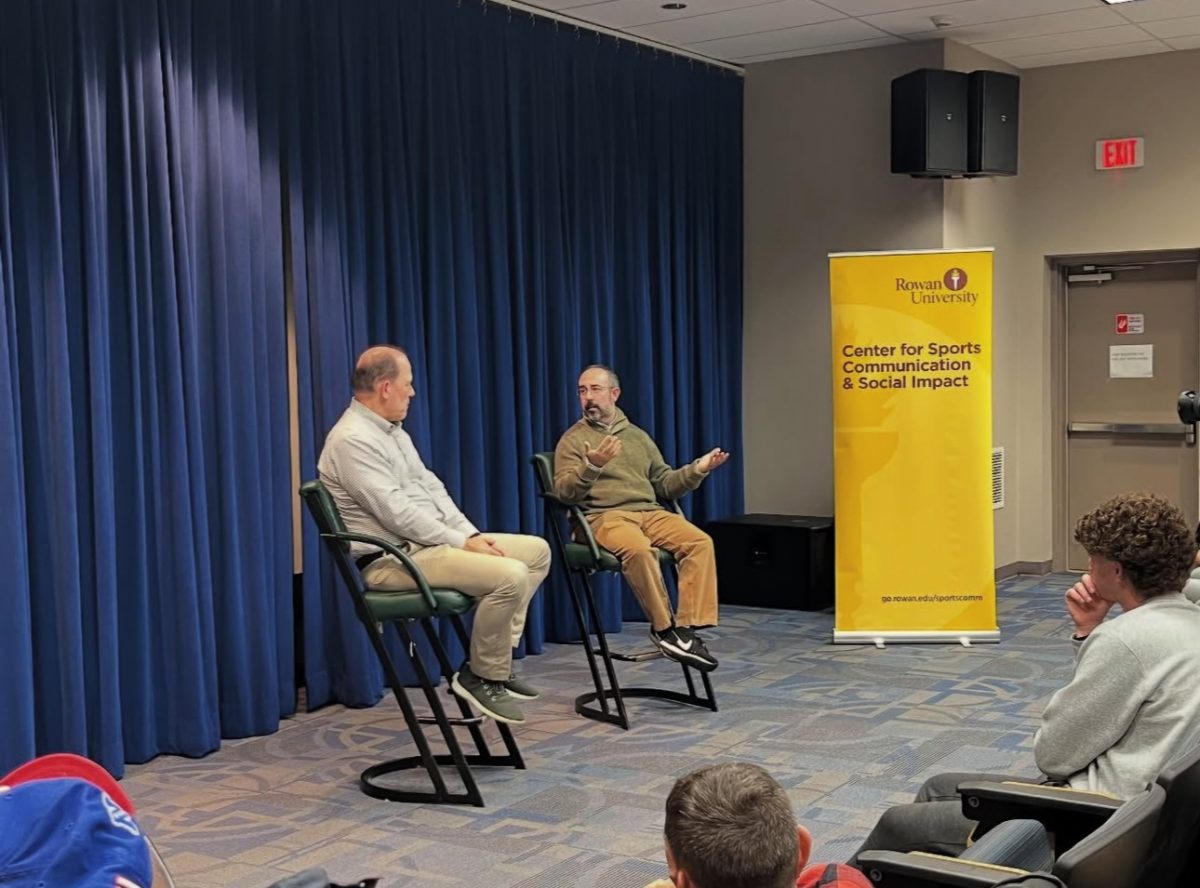

What happens when hateful rhetoric, college students and police converge?

Oh, you know, just another Thursday afternoon at Rowan University.

Well, to be fair, last Thursday’s protest was a bit unusual for our campus. Fox Philadelphia put the crowd estimate around 500 people.

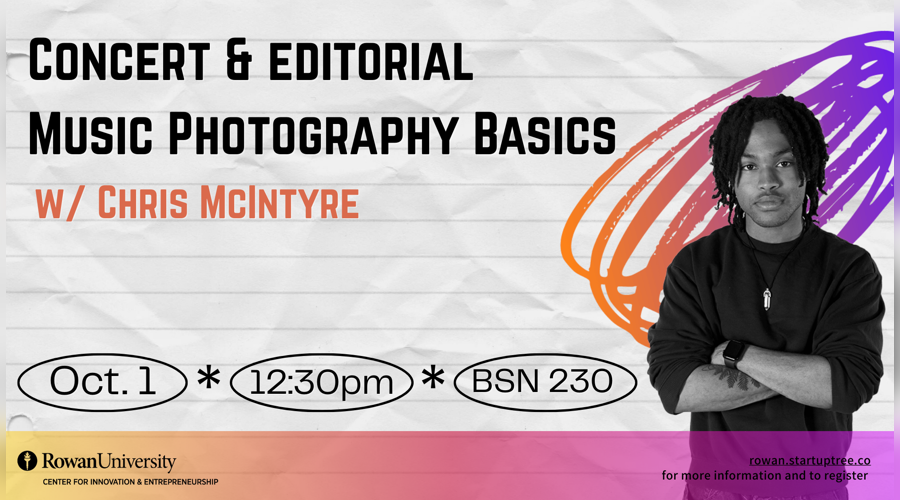

The crowd amassed because religious demonstrator Aden Rusfeldt and several members of his congregation came to Rowan with signs denouncing gay individuals, Muslims, masturbators and many other groups they deemed as sinners.

They also came with megaphones, preaching their narrow vision of an acceptable society to passersby. Overall, their rhetoric proved inflammatory and could be seen as what many in the modern age deem as “hate speech.”

Much of the dialogue that followed this event focused on why Rowan allowed these demonstrators to remain throughout the day, protected behind a police barricade.

Rowan President Dr. Ali Houshmand addressed this point in an email sent out to the university.

“Rowan is obligated as a public institution to allow freedom of expression, but we do not endorse or condone hate speech in any form,” Houshmand said.

While it might suck and be uncomfortable for students to face hateful rhetoric on their campus, the First Amendment protects most forms of speech, including what Rusfeldt and his followers spewed.

Several Supreme Court cases dealt with the bounds of free speech and led to the current state of what can legally be spoken. Schenck v. United States established the notion of a clear and present danger posed by speech, making punishable expressions which would likely manifest a crime.

Justice Louis Brandeis, in Whitney v. California, noted that citizens have the responsibility of partaking in the governing process. To do so adequately, they must be allowed to criticize the government (and, by extension, anything else) freely. If the government is allowed to punish or silence unpopular views, the overall society is much more negatively affected than what results from allowing offensive or divisive rhetoric to be spoken publicly.

Brandenburg v. Ohio sets our modern standard: speech is illegal if it

is “directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.”

Hateful people who spend their time travelling from college to college— putting forth speech deemed racist, homophobic and counter to our wider society’s values—are within their legal right to do so.

This might seem like a wholly unpleasant reality and may lead to a questioning of our Constitution’s intentions altogether. However, let’s step back and take a broader view.

All speech must be allowed in public places as long as it won’t likely incite lawless action, like calling for an assassination or threatening to specifically cause violence. Private entities (think workers in a company being forbidden from making racist statements to coworkers) and platforms (think Twitter establishing a policy of what’s allowed on its site) can place limits on what is allowed within their operations. Since Rowan is a public university, they must operate within the bounds of the First Amendment.

How, then, do we deal with hateful people who intentionally try to sow division and cause strife on our campus?

Perhaps there are three main ways by which people like Rusfeldt and his followers can be dealt with.

The most obvious and the one that might feel the best in the moment is with anger. This might mean screaming back at them, throwing soda on them (an act for which two members of the Rowan community were arrested) or calling for them to be banned from campus. This, of course, is not an ideal reaction. Meeting hate with hate never betters a situation. We sink to the level of the people we’re trying to denounce when we react in this default way.

The second option is to ignore them. This has its perks. Demonstrators like Rusfeldt crave attention, becoming almost caricatures of what a stereotypical religious zealot looks like. Wearing a shirt with the words homo and Islam crossed out in the restricted sign is so outlandish and counter to true religious values that it begs the question of whether Rusfeldt really holds religious convictions, or if he wants to gain notoriety. Further, he wore a hat that says “I <3 Haters.” Someone so obviously seeking to divide might not even be worth a giant protest and extensive media attention. If we protest and cover him, does that make him the winner in this situation by giving into his desires? Perhaps walking by and letting him preach into a void defeats his goal of affecting passersby.

The third option looks like what ultimately happened at Rowan last week, with students coming together to play music, dance, create supportive signs, eat free ice cream and turn the tense situation into an environment of acceptance and fun. In the darkness, the light of students and their value of acceptance shone through. While Rusfeldt was likely able to feed on the anger of some of those present, he was probably deflated at seeing the Rowan community stick together and support the groups he calls sinners.

Whichever of the three methods you prefer, it’s best to view situations like these in their entirety. We have free speech, which allows Rusfeldt to preach hatred on our public campus. Yet out of this terrible situation, the beauty of connection and love was able to shine brighter, becoming the true focus of the narrative. These polar opposites of hate and love are inherent to our world, and to have one, we must have the other.

Out of any situation that seems steeped in hatred, we’re always mere steps or actions away from rising strongly in love.

For comments/questions about this story, email [email protected] or tweet @TheWhitOnline.