Around the time that AI (Artificial Intelligence) was becoming popular, and ChatGPT had just hit the mainstream, people in my life started forming opinions about it. Primarily, one of my mentors, who seemed to enjoy telling anybody who would listen that “AI is the devil.”

As much as I love the chaos of a burnt bridge, it seemed counterintuitive to get her riled up, so I would just smile and nod.

Sure, AI is the devil.

But, realistically, AI was really new and seemed pretty unassuming, and maybe even useful. I knew people who used it to write emails or generate outlines, and I myself used it to write the framework of a speech.

It seemed like the devil was really in the details. And perhaps AI was helping to streamline the writing process and keep us writers and creatives from getting bogged down in the nitty-gritty of big ideas.

Well, it’s been a year, and I can safely say that that’s just not true. AI is no longer a niche tool useful for the high school cheater or lazy emailer. It’s a vessel for forgery and imitation, it can be used as a content farm to constantly generate digital media, and it’s coming for jobs. A lot of them.

It may not be the devil, but AI was definitely Pandora’s box. Now that it’s open, it’s time to assess the value that it brings to the table, and ultimately decide if that value holds up against its drawbacks.

An article by the University of Illinois, Chicago defines artificial intelligence as “represent[ing] a branch of computer science that aims to create machines capable of performing tasks that typically require human intelligence.”

AI can then be broken down into subsets, although overlap does exist. The general consensus though is that the machine is adapting to solve problems rather than relying solely on code.

So, for example, if you ask a calculator to solve 2+2, it will spit out 4 because it has a laundry list of code that the machine is running to eventually find the answer. It’s procedural.

If you ask AI to solve 2+2, it will analyze a database of “knowledge,” and use what is called Natural Language Processing to come to an answer, similar to how a human will make inferences, rationalize, or generalize using our preexisting knowledge.

Simply put, AI is being designed to imitate human brains.

In its early stages, AI was really bad at this process of imitation. You could ask a program like ChatGPT to write a list of ingredients for spaghetti and it would give you a bunch of nouns related to Italian food in no specific order. Pepperoni, parmesan, pasta, tomatoes, basil, etc.

Today, I asked ChatGPT, to “write a list of ingredients for spaghetti” and it gave me, in list format, ten ingredients that do go in spaghetti, and even in order of importance with the optional ingredients at the bottom. This is, on its own, not very alarming. But how did AI get better?

Corporations like OpenAI have been training models on whatever is accessible to them on the internet, in a process known as web scraping. Web scraping could mean the downloading of a web page for an AI to analyze the text, or meta mining public Instagram posts for images to add to data sets.

But, it’s not just your photos that are training AI. Your habits, purchases, media consumption, likes and dislikes, and the list goes on are all also training AI. As are mine, and most other people’s. Your data is a commodity, after all.

There is an argument to be had that this training is in violation of copyright laws, and some people are having it. The New York Times, for example, is currently in a legal battle with OpenAI over the alleged usage of their articles to train AI.

For the time being, however, it seems that a parasitic relationship between AI and creatives (and on a larger scale, humanity as a whole), is going to endure. It’s training on creators’ visual artworks, photographers’ photos, authors’ writings, musicians’ recordings, and composers’ compositions to name just a few of the works being incorporated into data sets.

After the AI is trained, they can usurp these creators themselves by cheaply producing “original content” using complex neural networks.

I had a conversation with my own mom about this usurping, telling her that my future was endangered. She seemed surprised that live performance (my hopeful line of work) would be at risk of a takeover that is seemingly entirely online.

Playwriting, composing, and even the generation of promotional materials, however, are all at risk of being swallowed up by AI. And, my work is not always just on stage. I’m all sorts of things: an author, poet, singer, songwriter, composer, actor, and occasional dabbler in the visual arts. I can soundly say that all my passions are at risk, even if the stage itself is safe, for now.

Most companies do not consider the passion behind the work their employees do. The New York Times may be feeling litigious but I guarantee it is not on the behalf of their employees’ love for writing, but the monetary threat having their work used to train AI presents.

The other side of that coin, however, is the monetary boon AI can be. The start-up cost of an AI model cannot possibly be cheap, and yet the labor that it can replace is immense.

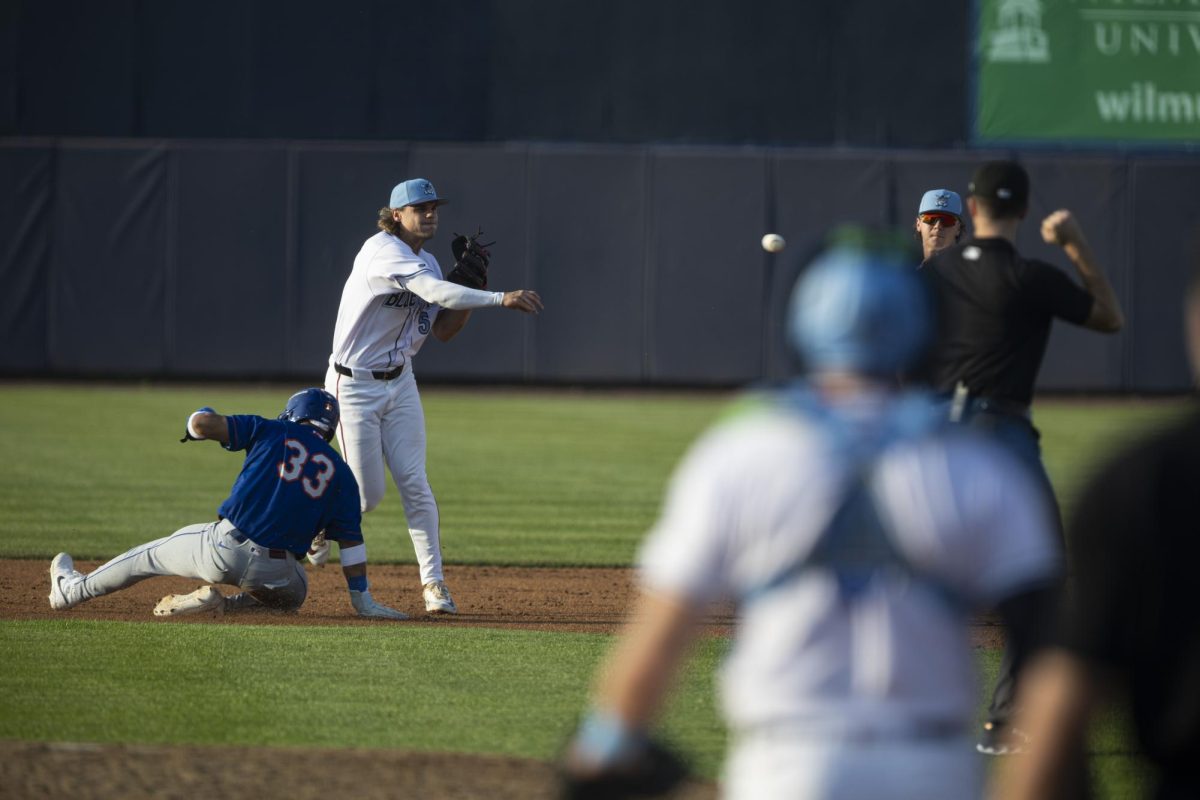

An AI can create made-to-order copyright-free images with no downtime, replacing the need for photographers, models, editors, or image hosting platforms. It can write an article, or 2, or 10000 in whatever style you ask it to, incorporating knowledge from its vast array of data, replacing the need for writers, editors, or researchers. It can create music in any musician’s style, with original lyrics and instrumentation.

That sounds awesome, and in a vacuum it is. You can find AI covers of deceased or living artists “covering” another band’s song, like AI MUSIC WORLD’s rendition of Frank Sinatra singing Smells Like Teen Spirit by Nirvana.

In reality, it’s disturbing. How many jobs are on the line because a computer can do it in a fraction of a second? It doesn’t matter if the image feels a little “off,” or if the music is a little kitschy, if it’s vastly cheaper to just have a computer make it.

This is without touching on how easy it is to create work that sounds or reads or looks like it’s been created by an artist, even if it hasn’t.

The implications of creating work that uses someone’s creative voice, without their consent, are too vast for this article. So I ask you to consider them for yourself and draw your own conclusions.

Passion has always been commodified. We live in a post-industrial society and have seen in real-time the effects of industrialization in the workplace. A community doesn’t play host to a cabinet maker, a cobbler, and a tailor. Instead, this work has been primarily outsourced to regions where labor is cheaper and the factories are automated. Ikea usurped the handcrafted.

Now, we are in the midst of a second revolution, one which will now take over the cerebral. Artists, of course, are not going to go away. Some people managed to find their niche even as factories took over. Prices, of course, rise to reflect that. The cost of a handcrafted piece of furniture, for example, is quite prohibitive to the common American. Simultaneously, the cost of being an artisan is also prohibitive to the common American. Artisans become rarer.

I don’t know how artists of today are going to adapt to the great wave of replacement that is set to occur, but it’s not going to be pretty.

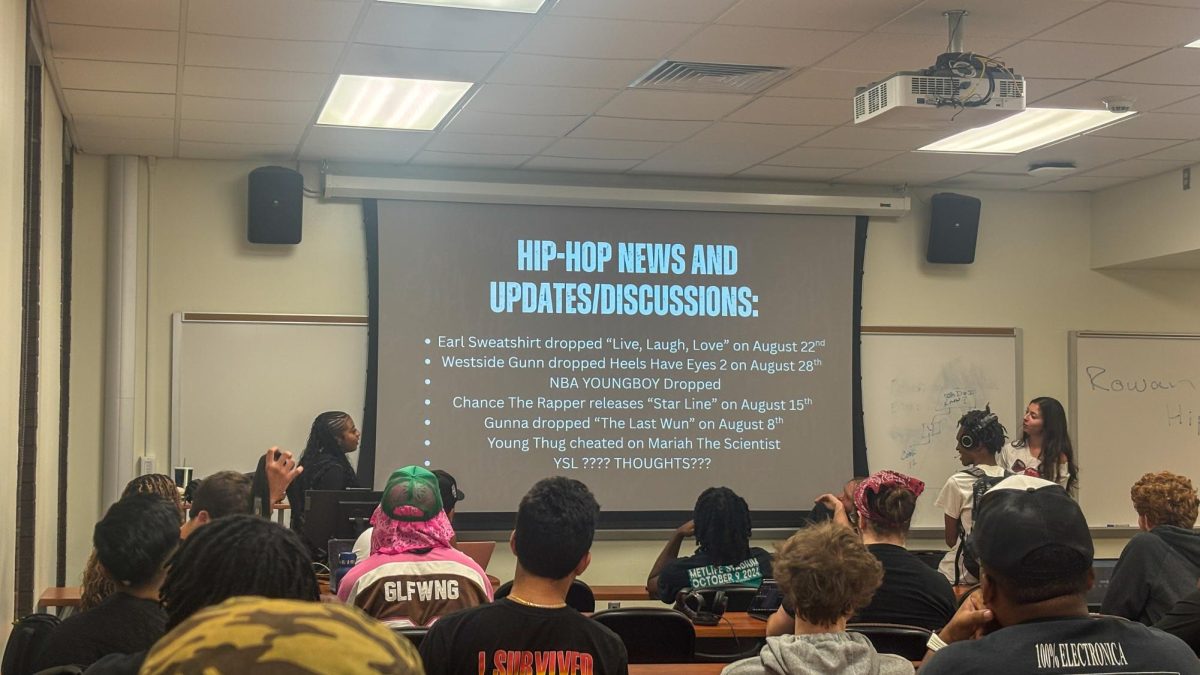

As a college student, I’m surrounded by the next batch of workers and I see that the waters we face are murky. What jobs we’ll have available to us may change vastly in the AI landscape, and quite frankly it’s not fair.

No one is guaranteed work in their field, but I don’t think it’s unreasonable to hope that with a little effort, someone can find it. Thanks to AI, now it’s uncertain if some fields will even exist, leaving entire groups of people without steady work. This replacement is unconscionable to support.

That is why I’m boycotting AI.

John Adams wrote, “I must study politics and war, that our sons may have liberty to study mathematics and philosophy. Our sons ought to study mathematics and philosophy, geography, natural history and naval architecture, navigation, commerce and agriculture in order to give their children a right to study painting, poetry, music, architecture, statuary, tapestry and porcelain.”

Why should we turn back, and allow a computer to study the arts? So that humans can regress? No. AI may be an impressive feat of computing and mathematics, and it may be able to create some amazing things, but so can humans. And humans, fortunately, and beautifully, have passion to go along with skill.

There is value in that pursuit of creating for creation’s sake. The product, fortunately, just so happens to have value as well. In a capitalist society, we should seek to protect that value, so artists can continue to use their work to live.

This article was written by a human, for humans.

For comments/questions about this story DM us on Instagram @thewhitatrowan or email [email protected]

Heather Galvano • Mar 13, 2025 at 11:55 pm

I agree as well!!! Thank you for writing this!!! I feel the same and don’t understand how/why everyone is jumping on board when it seems so obvious how dangerous it is long term.

Elaine • Nov 17, 2024 at 7:48 pm

I agree wholeheartedly. I’m a retired graphic designer and understand more than some, and am good at spotting a fake. I’ve seen many in Facebook, and actually corrected a friend who was believing a picture until I pointed out the shadow differences. People are already believing hype, both personally and politically. But the worse part is far reaching job loss which will bleed down to a host of other areas, like college attendance, economics, more health issues, drugs, lack of mental stimulation not knowing truth from lies – it could be endless. I know that sounds catastrophic, but I think those reaching college age may be having to reassess their looming careers. School career counselors need to be on their toes. I’ve already talked my niece out of going into graphic design because there is such a glut of art online for companies to use, and when their bottom line is getting low, artists are the first to go. She’s a nurse now.